LUNA: Beyond the Arena

Published December 15, 2021

Juan Luna is the most celebrated Filipino artist in history. A subject of Spain from the colonies who, against all odds managed to shine in the 1884 Exposición General de Bellas Artes in Madrid, making a statement for himself with his grand masterpiece, the Spoliarium - A massive painting depicting fallen gladiators, that currently hangs in the National Museum today.

But beyond this seminal piece of art, there is more to Luna than his iconic piece. In fact, his style is greatly influenced by his life and attitudes towards colonialism, and serves as one of the reasons why his work, along with his contemporaries, resonate with audiences and retain their relevance.

The Philippines under Spanish Rule

After transferring the administration of the Philippine Colony from the Viceroyalty of New Spain to Madrid in 1821, the Philippines’ value to Spain was brought into question. Largely an agrarian colony, it did not contribute in any significant way and the option of Spanish control being relinquished in the islands was a very real possibility. However, apart from the potential of the Philippines its trade routes, the desire to replicate Spanish culture and dominance over a perceived inferior race proved too great an incentive to retain the colony, but not enough to further invest in the infrastructure, and education of those under their dominion.

It is clear in the works done during the revolutionary period that started in the middle of the 19th Century, that a seismic shift in attitudes coincided with the rise of Spanish Liberalism. Illustrados, or the Philippine ruling class, composed of affluent Filipino mestizos began making their way to the mainland and began to pursue higher learning in Madrid. There they were exposed to the prevailing styles and forms of art that initially became the template for their creative self-expression.

Luna, an Artist in Madrid

Traveling to Spain with his brother Manuel, Juan Luna pursued further training at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, paving the way for his career as a painter in Europe. Predating The Spoliarium, Luna’s La Muerte de Cleopatra (1881) offers a peek into the artist’s initial attempt to create pieces targeted towards a specific audience. The historical subject, composition, bright lighting, and controlled hand reminiscent of the classical style popular throughout Europe is writ large across the brilliant canvas. The subversiveness of the exaggerated tilt and angle of the slave’s reaction to the tragedy before her, seems to defy the laws of gravity and conveys a violent, almost comical comment on the scene. From here we see his work and style evolve.

Spoliarium

The massive work, spanning over 7 meters wide and 4 meters tall, took 8 months to make. The subject is groundbreaking for the time: a glimpse of an unseen world, the Spoliarium (1884) of the great Roman Coliseum. The setting is a sort of antechamber where fallen gladiators are processed, stripped of their armor, finery, and weapons prior to being turned over to their grieving families and friends. The work was awarded one of three gold medals in that year’s Madrid Exposición General de Bellas Artes, a first for a native Filipino artist. Coupled by the fact that another native Filipino, Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo was awarded a silver medal in the same exhibition for his work Las Virgenes Cristianas Expuestas al Populacho (1884), this was cause for great celebration for the expatriate Filipino community in Spain at the time. It proved: at least for Spain and its colonies, that people from their dominions can paint just as well as, if not better than those from the peninsula.

The Spoliarium is a grim work, with its lighting alluding to the subterranean setting, it shows extreme tension in the center of the piece: drawing your eyes to the bright crimson robes of the slaves dragging the fallen into the space, with the swarm of onlookers on the left. The azure robes of the quiet mournful woman on the right hand corner, where the darkness hides the mangled remains of another gladiator, complements the lurid curiosity of the two old men staring off to the left.

After Spoliarium

Luna, after winning the historic gold medal, secured grants and commissions that kept his working well into the latter years of his life. It also provides a compelling picture as to the development of his style and how it defined him as an artist. His El Pacto de Sangre (1886) and La Batalla de Lepanto (1887) are studies in contrast. The El Pacto de Sangre is a work created by Luna as part of his four-year pensionadoship with the Ayuntamiento de Manila. In it, his mastery of dramatic, almost cinematic lighting is best seen. With the light source placed at an almost extreme horizontal angle, allows for the central figure of Miguel López de Legazpi to literally shine out of the darkness, along with the phalanx of armed and armored men off the side. It’s curious how the composition of the scene, one can be forgiven for forgetting that on the other side of the table sits Datu Sikatuna, hinting at the gross disparity within the power dynamic between these two leaders and the nations they represent.

La Batalla de Lepanto, on the other hand is a commissioned work for the Spanish Senate, at the behest of King Alfonso XII of Spain, depicting a Spanish victory over the Turks in the Battle of Lepanto. Here Luna showcases the fantastic use of space, depth, and perspective to convey the feeling of scale to an otherwise chaotic scene. The prow of a Spanish galley that breaks a Turkish formation is a breathtaking sight in what would become the last major maritime battle fought between rowing vessels.

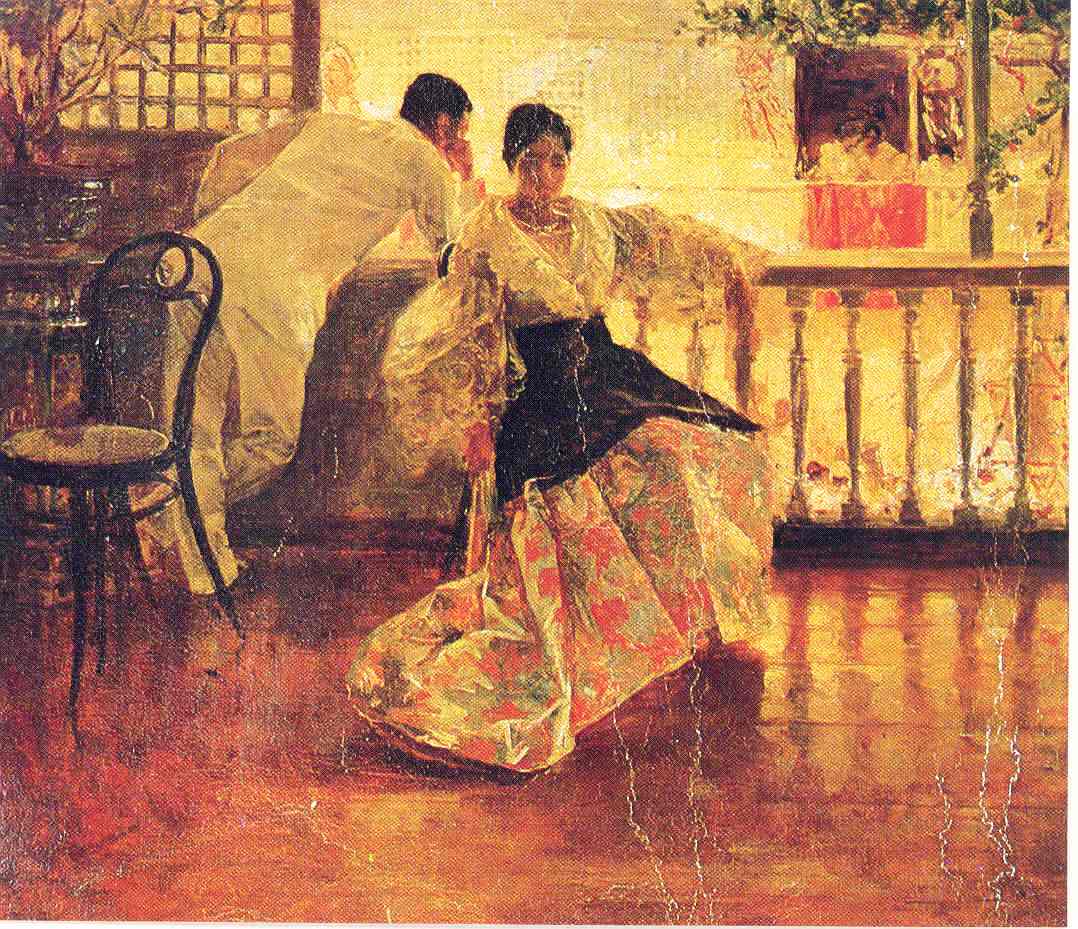

Luna and the rise of Philippine Nationalism

With the death of Rizal in 1896, a large chunk of the intellectuals who have since been vocal about reforms within the Spanish colonial framework openly advocated for complete independence instead, it was during this time of great civil unrest that Luna embraced a style that was closer to his roots. With his coy, romantic Tampuhan (1895), Luna depicts a simple scene involving two lovers engaged in a spat. The deliberate, strong brushstrokes, defined by his earlier works bring a certain texture and quality to this slice-of-life piece, elevating it to those of his more well-known masterpieces. The bahay na bato is an iconic feature of upper-class Philippine life, one that is quite familiar to Luna as an Illustrado, and is characterized here by the wide windows that light the entire canvas, overlooking the street, so much so that it actually reveals the comings and goings of the house right across it.

Luna would pass away due to a heart attack in Hong Kong in 1899. His death coincides with the year the Philippines declared its independence from Spain in the midst of the Spanish American War. His works remain as examples of how art can be used as a catalyst for a nation’s self-determination. His career helped bring greater awareness and recognition for the colonies and their contribution to art, literature, and culture for the glory of Spain, and eventually, a fully independent Philippines.