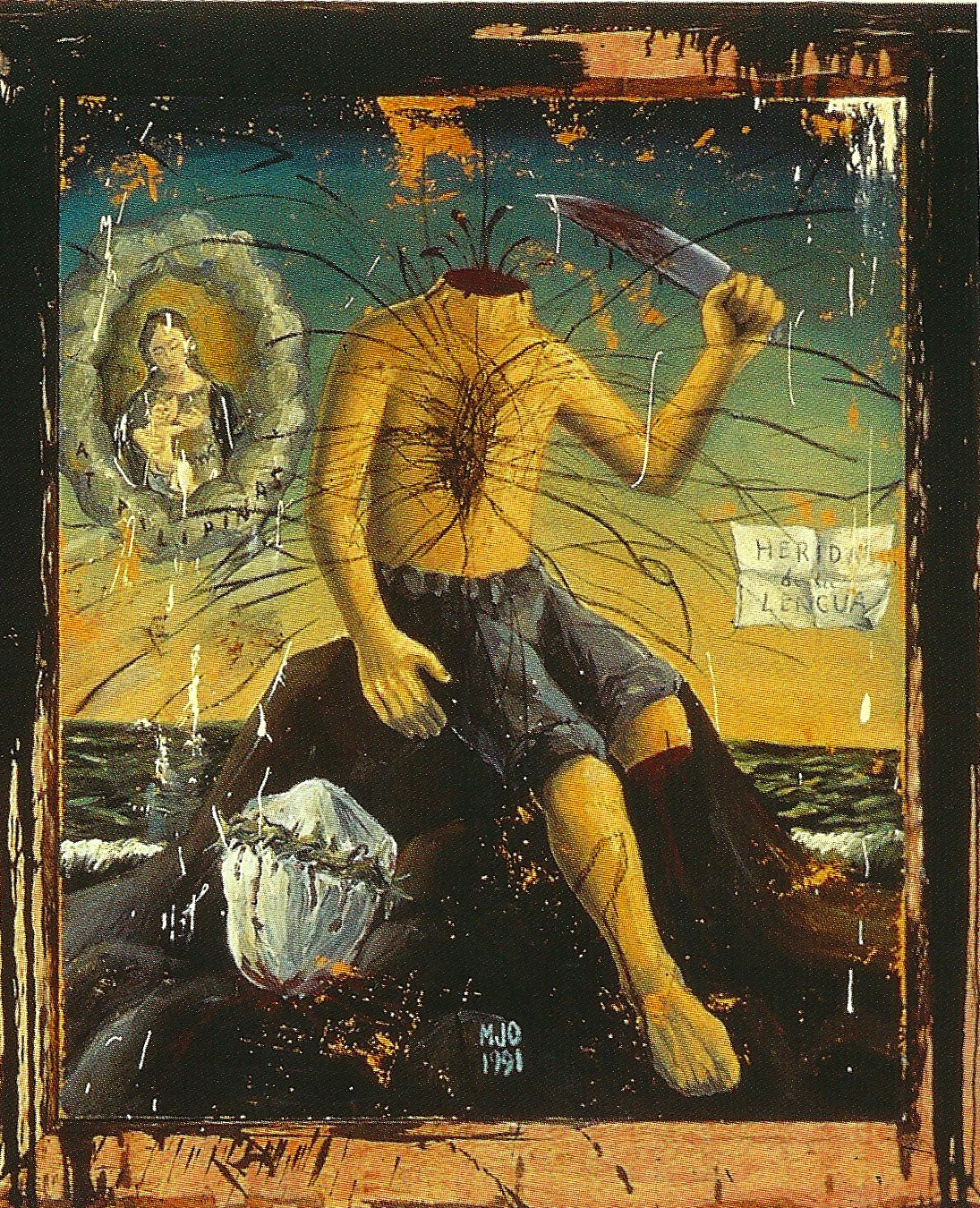

Manuel Ocampo

Published July 28, 2022

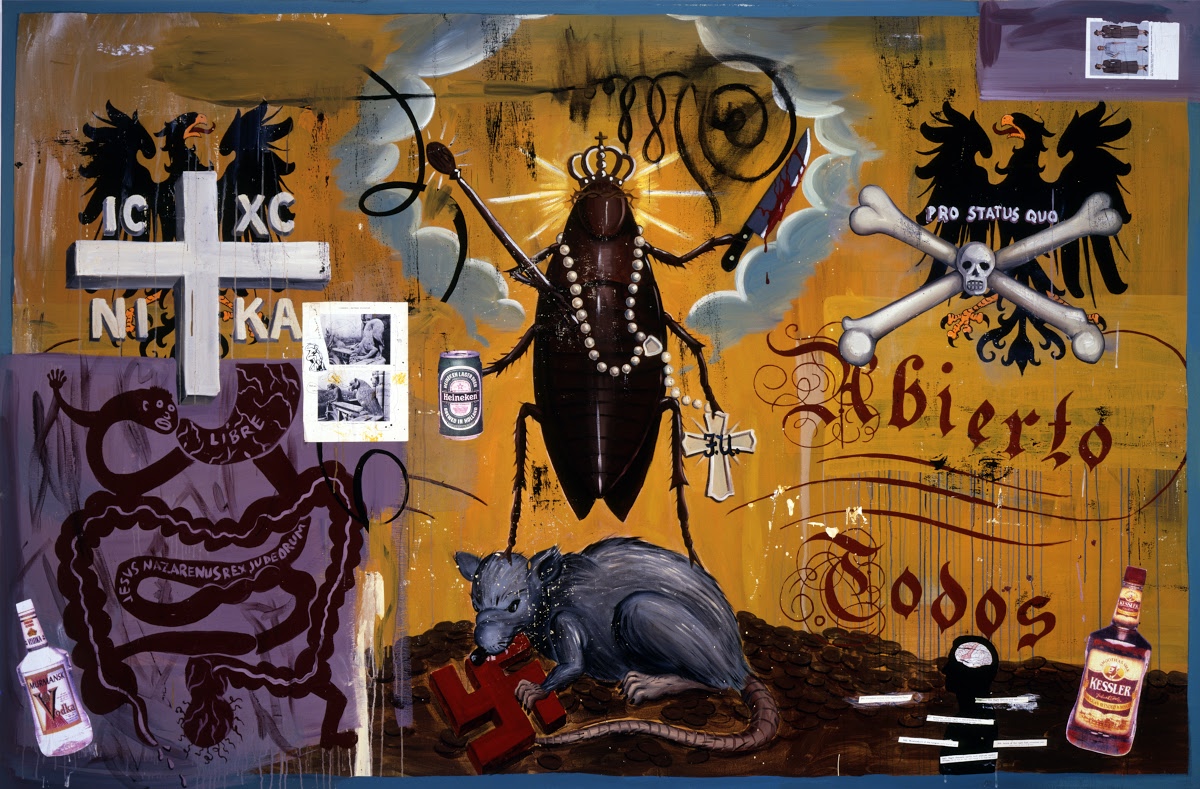

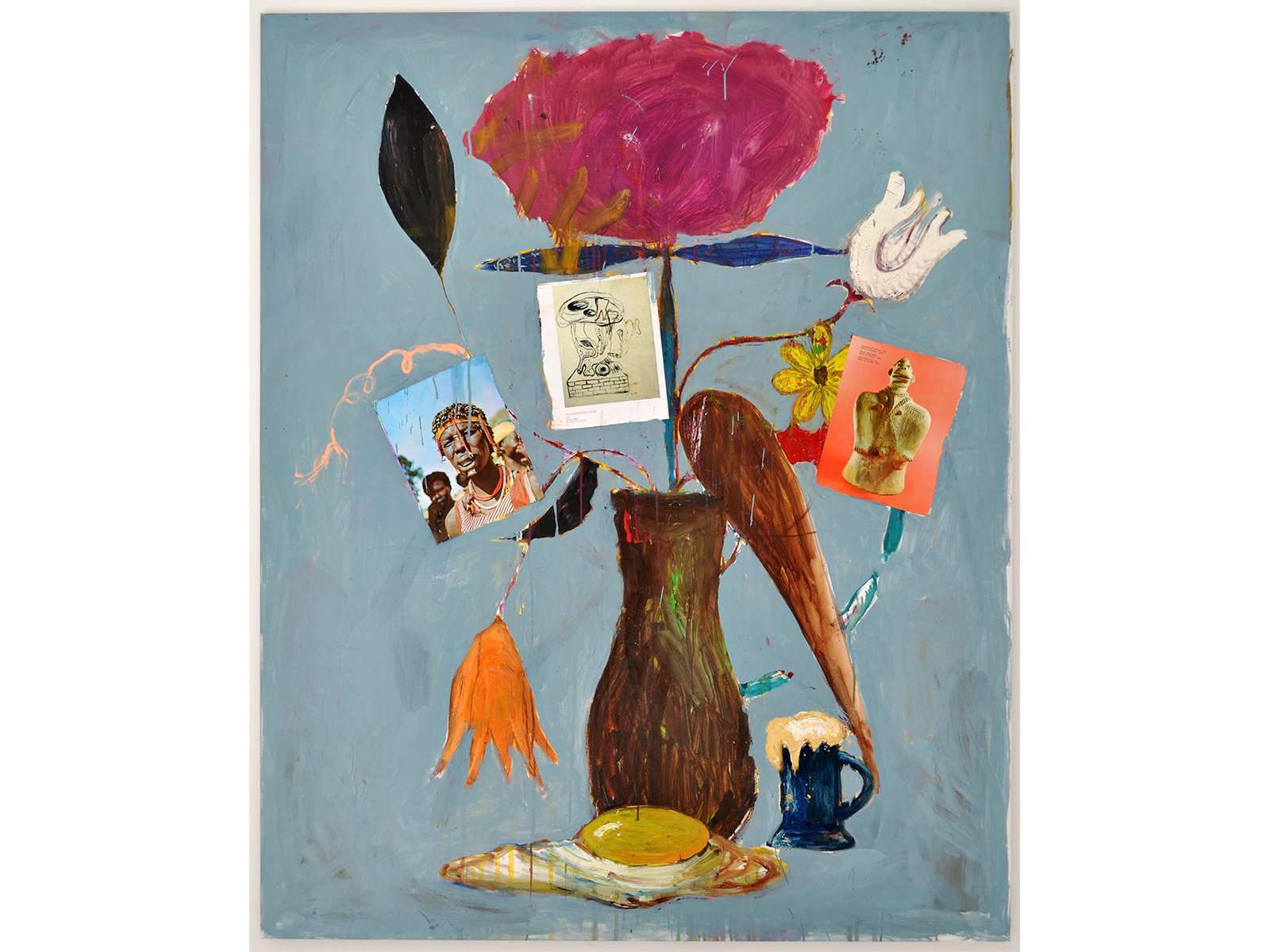

First of all, Manuel Ocampo is a bad boy. An artist mutineer whose work toggles between retinal thrill and ontological mystery. Ocampo uses motifs from popular western iconography, religious symbols, Filipino kitsch, art history, and punk subculture. Drawing from political allegorists such as Leon Golub, Géricault, Daumier, R. Crumb, Philip Guston, as well as Martin Kippenberger, Ocampo’s opus is loaded with tragicomedy enough to question, provoke, and arouse curious minds. Beyond that, his works summon a spirit of rebellion that permeates tradition, social convention, beliefs, attitudes, and bygone perceptions of beauty and order.

Secondly, Ocampo has become a revered art rockstar both in his homeland and across the globe. While he rejects this recognition, his influence on his contemporaries and followers endures and continues to impact the scene. According to Ocampo, his expression is a statement of existence where one person’s blasphemy could be another person’s form of spiritual assertion. This is evident in his beginnings as an artist as he became part of the a new breed of artists who were veering towards a different direction, away from the career-oriented experiments of the New York scene into deeper introverted articulations of both banal and multicultural experiences in the contemporary West.

Ocampo’s work takes guts, proper doggedness, a certain amount of bluster, brazenness, and intractability. And over the years, he has challenged the grandiosity and reverence of fine art, especially paintings. With his rough, antagonistic, and irreverent approach in skill and theme, Ocampo has had his share of controversy in the 1990s, disturbing established taste and values regarding art and conventions tied to it. Consequently, this spurred a lasting and profound impression on the blurred lines between “good” and “bad” art. When it comes to creating, there are no rules. And whether he wants to combine religious icons and supermarket brands, body parts, vultures, bones, and buzzards, this approach will continue to explore post-structuralism and hold sway over the interpretation of visual language.

Manuel Ocampo is one of the most internationally-acclaimed Filipino artists whose works often combine sacred Baroque religious iconography with secular political narratives. His works have also been used in music album covers of musicians and bands such as Beck and Skinny Puppy. He has exhibited extensively throughout the 1990s, with solo exhibitions at galleries and institutions through Europe, Asia, and the Americas. In 2005, his work was the subject of a large-scale survey at Casa Asia in Barcelona, and Lieu d’Art Contemporain, Sigean, France.

Ocampo's work has been included in a number of international surveys, including the 2004 Seville Biennale, 2001 Venice Biennale, the 2001 Berlin Biennale, the 2000 Biennale d’art Contemporain de Lyon, the 1997 Kwangju Biennial, the 1993 Corcoran Biennial, and 1992's controversial Documenta IX. His work was featured in many group shows in the 1990s, including Helter Skelter: LA Art of the 1990s, at Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 1992; Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art at the Asia Society, New York in 1994; American Stories: Amidst Displacement and Transformation at Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo in 1997; Pop Surrealism at the Aldrich Museum of Artin 1998; and Made in California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900-2000 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2000. He has received a number of prestigious grants and awards, including the Giverny Residency (1998), the Rome Prize at the American Academy (1995–96), National Endowment for the Arts (1996), Pollock-Krasner Foundation (1995) and Art Matters Inc. (1991).

Main photo by MM Yu