Lucian Freud

Published May 30, 2022

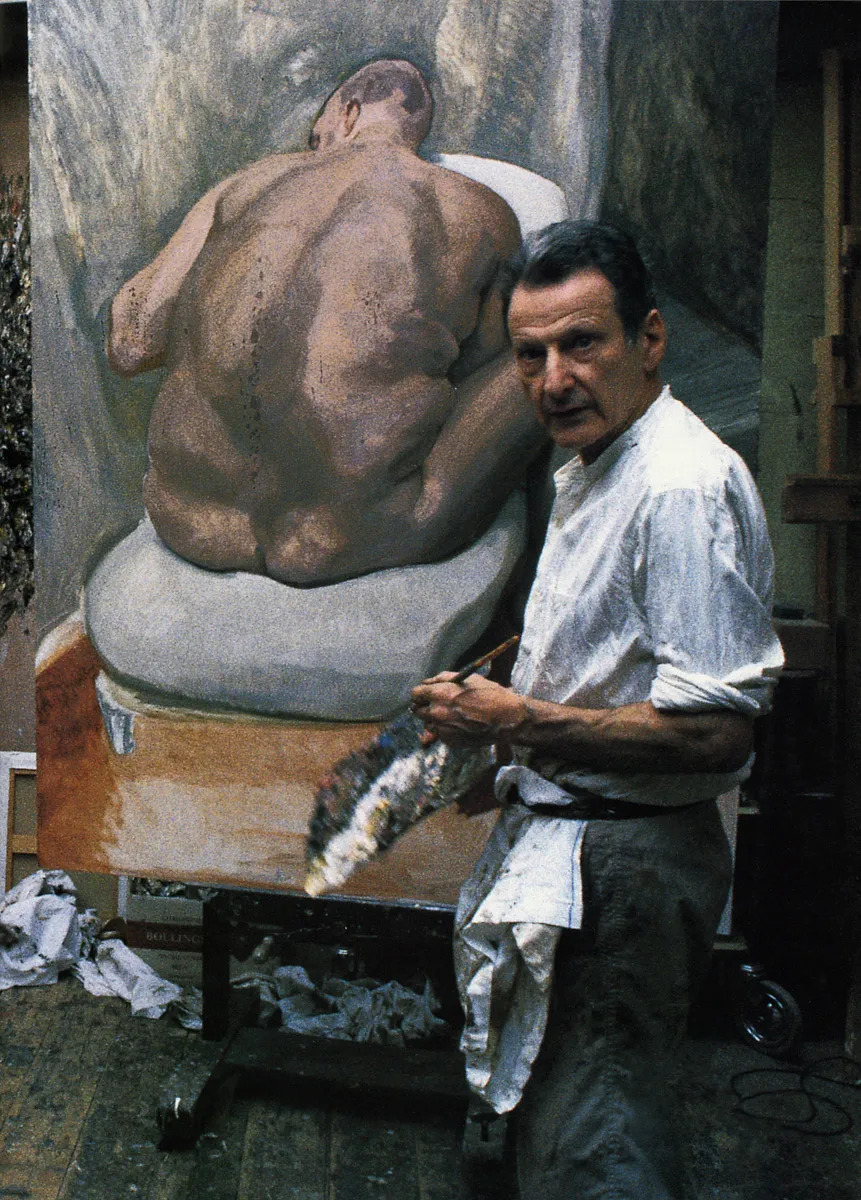

Considered a hot-headed Narcissus, Lucian Freud painted big bodied subjects in keeping with the realist tradition. They are generally somber and thickly impastoed often in unsettling interiors and urban landscapes. With his insistent detailing and conventional, deliberate slapdash illusionistic approach, his works display a provincial and retardataire sensibility—a local taste, like warm beer.

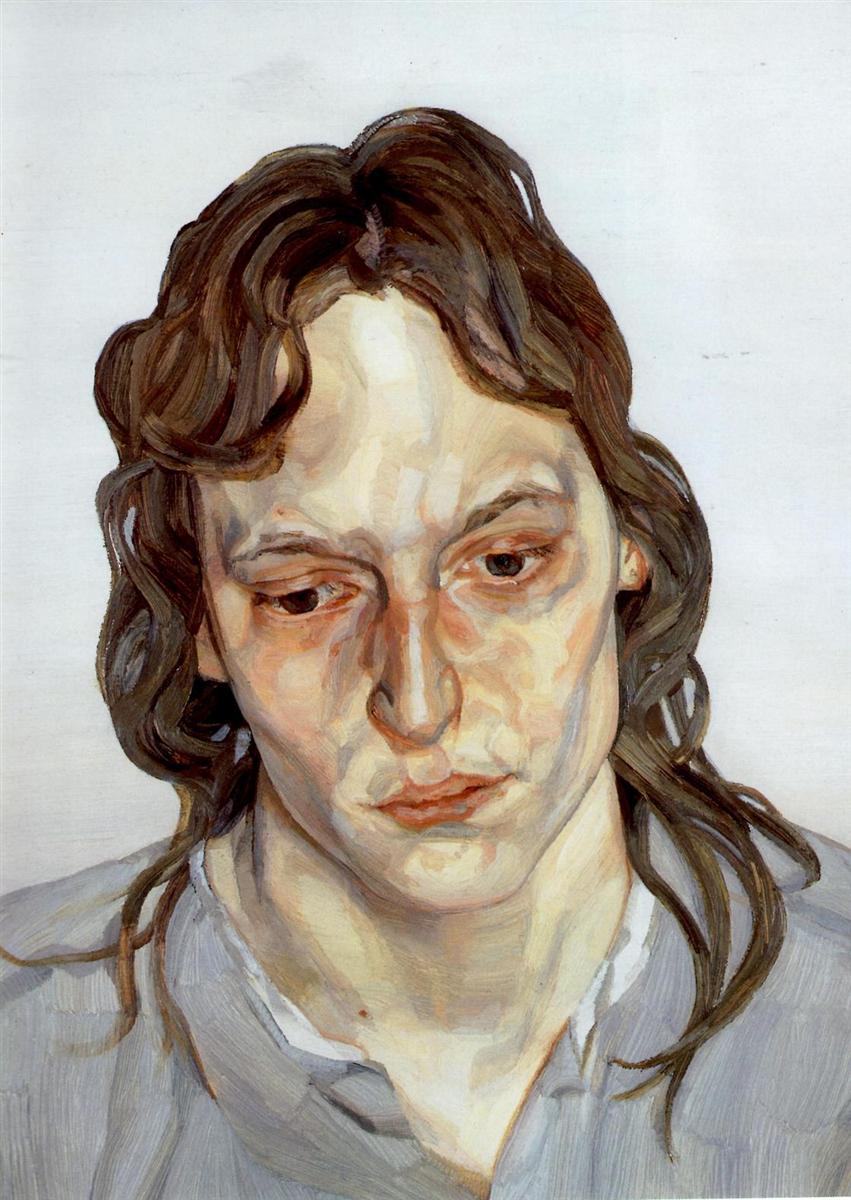

Freud was the son of the architect Ernst Freud and the grandson of Sigmund Freud. He was trained at the Central School of Art in London where he was known for his unorthodox behavior as for his drawing talent. He turned to painting full-time after World War II. Despite his unconventional trajectory, there was a recognizable authority to what he painted early on. Choosing painting was an affirmation of the body over the brain, a way of rejecting his father’s and his grandfather’s more intellectual manners. He quickly evolved a faux-naïf style with sharp outlines, flat surfaces, and a folk-art treatment of figure and face. Many of Freud’s works had to do with the human figure rendered in a realist manner and imbued with a stark and evocative psychological intensity. He made numerous portraits of his friends and associates as well as members of the British gentry. His series of paintings and drawings of his mother are particularly frank and dramatic studies of intimate life passages.

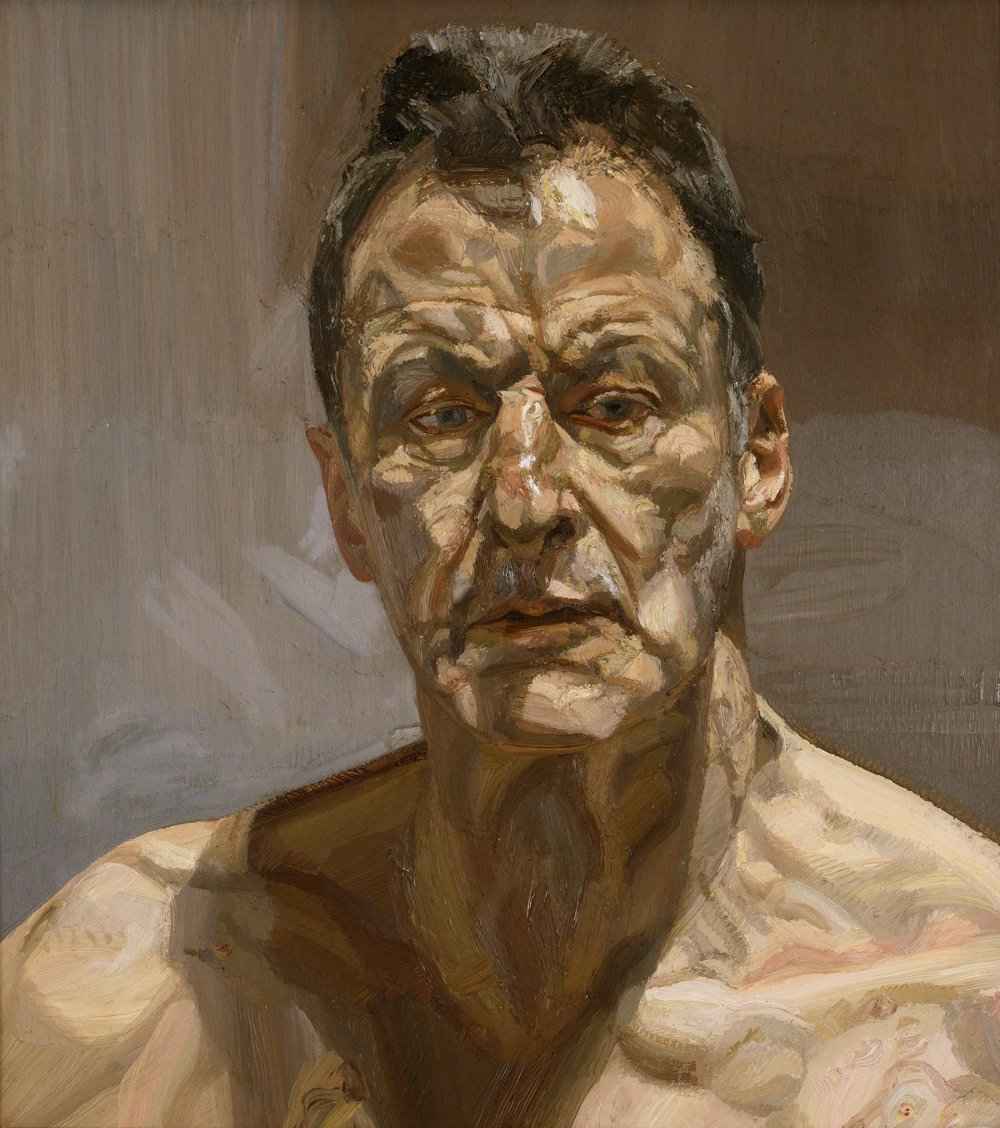

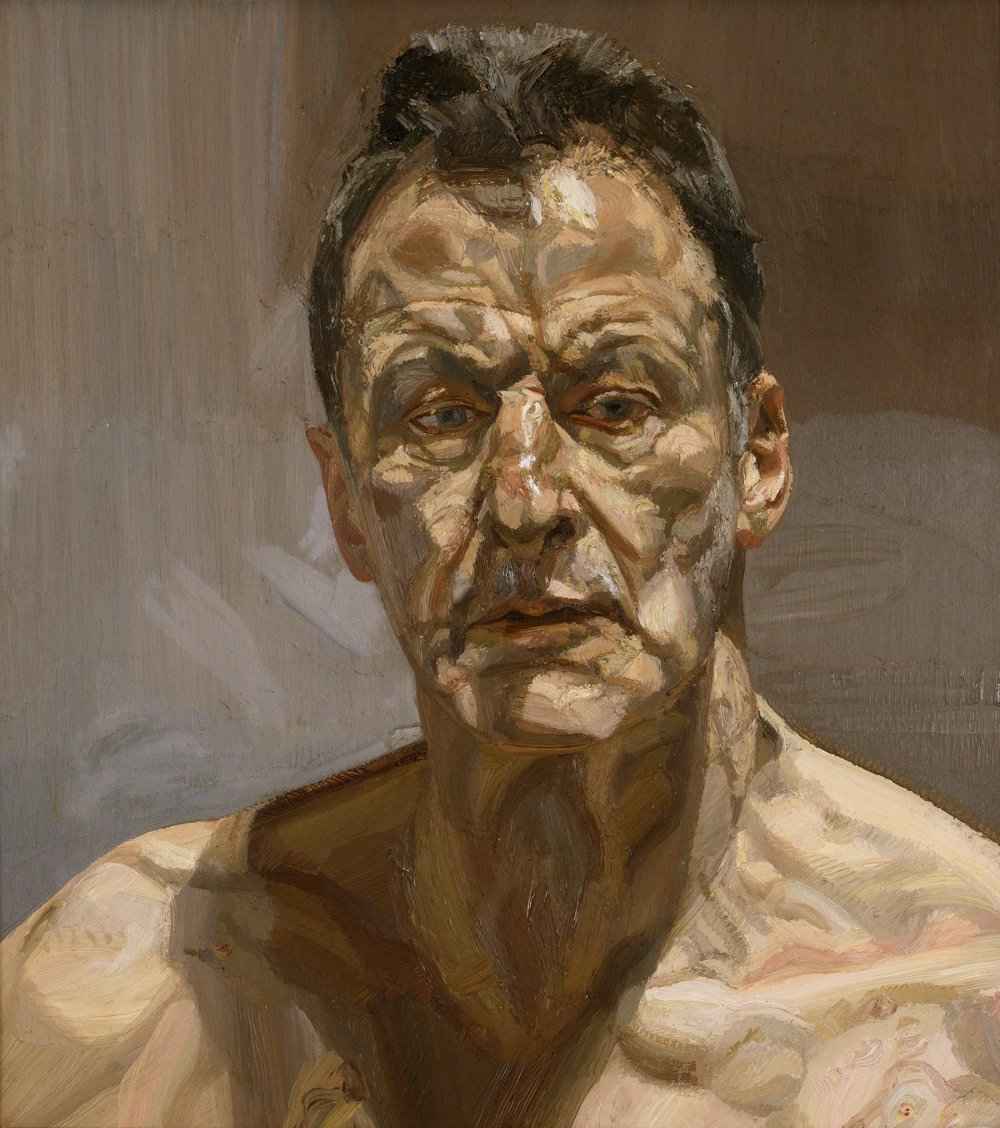

It has been said that Freud’s best works are those of the fifties when his stark-edge images of poignant futility hadn’t yet been overwhelmed by his appetite for expressing the same emotion exclusively in human fat. Freud’s gaze is perfectly reproduced in his conversations: not cruel, but never flattering. They show exactly who Freud was and what he felt. For instance, his portrait of Queen Elizabeth II caused controversy as it was rendered in an unflattering manner and people expected to see more royal dignity. It was a close up of the queen’s face with pearls on her neck and a crown which wasn’t supposed to be there but Freud decided to add it while working on the painting. He stated that on the interconnection of touch and sight that “you only learn to see by touch, to relate by sight to the physical world. I look and look at the model all the time to find something new, to see something new which will help me”.

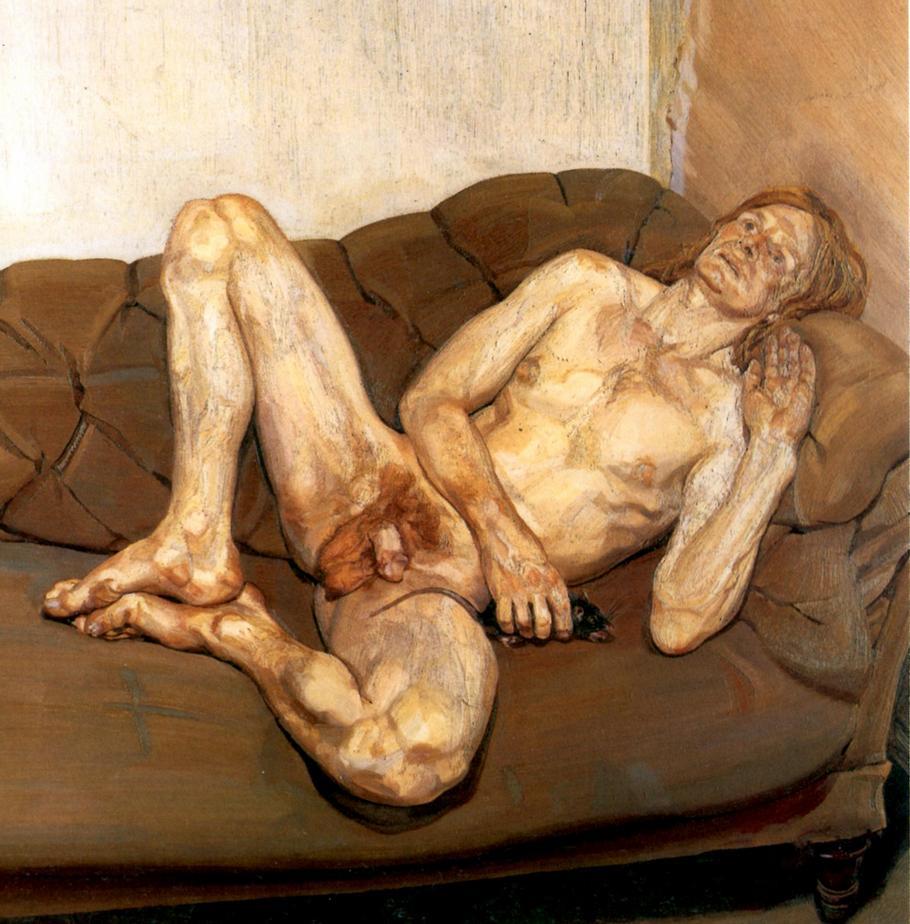

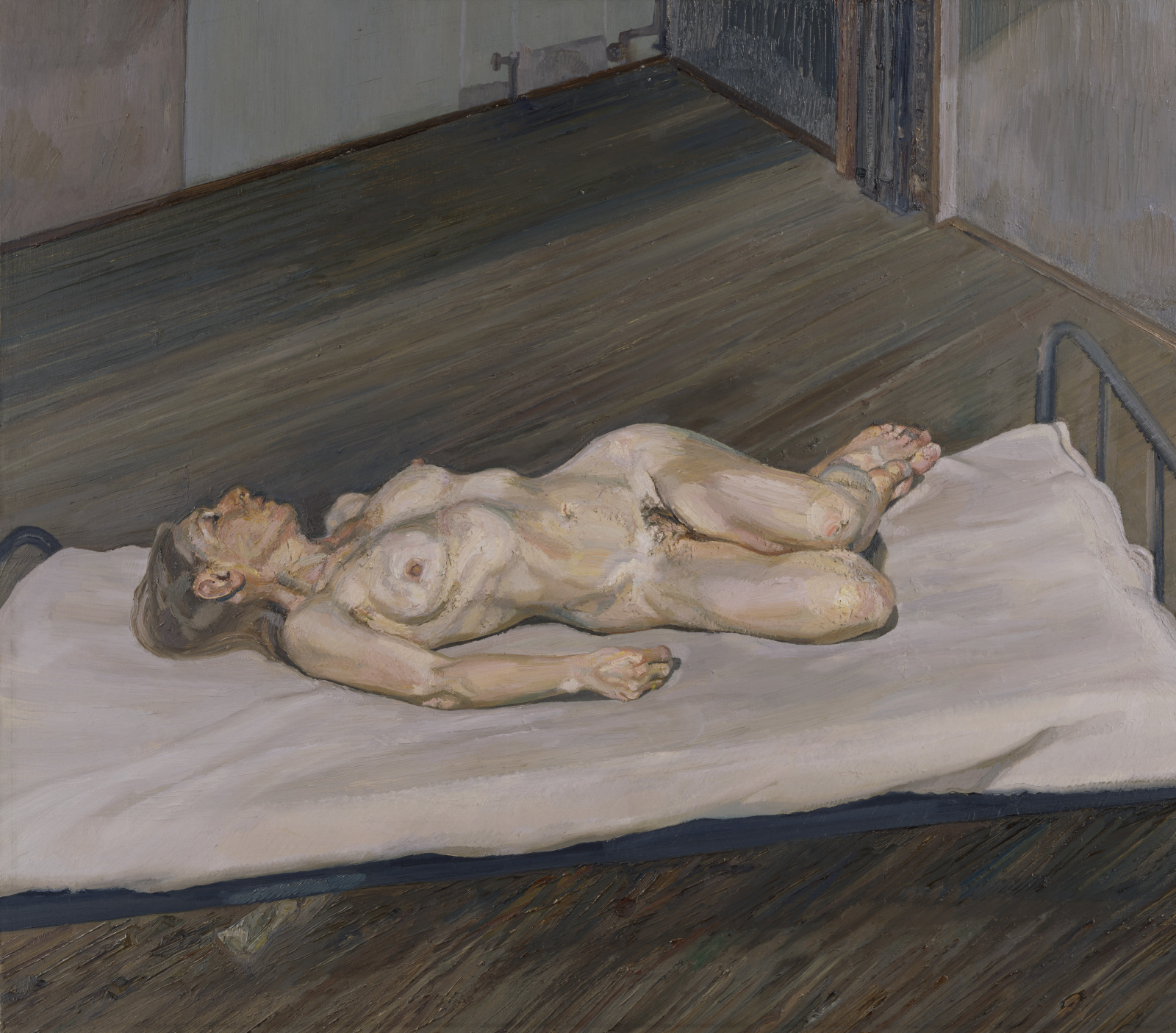

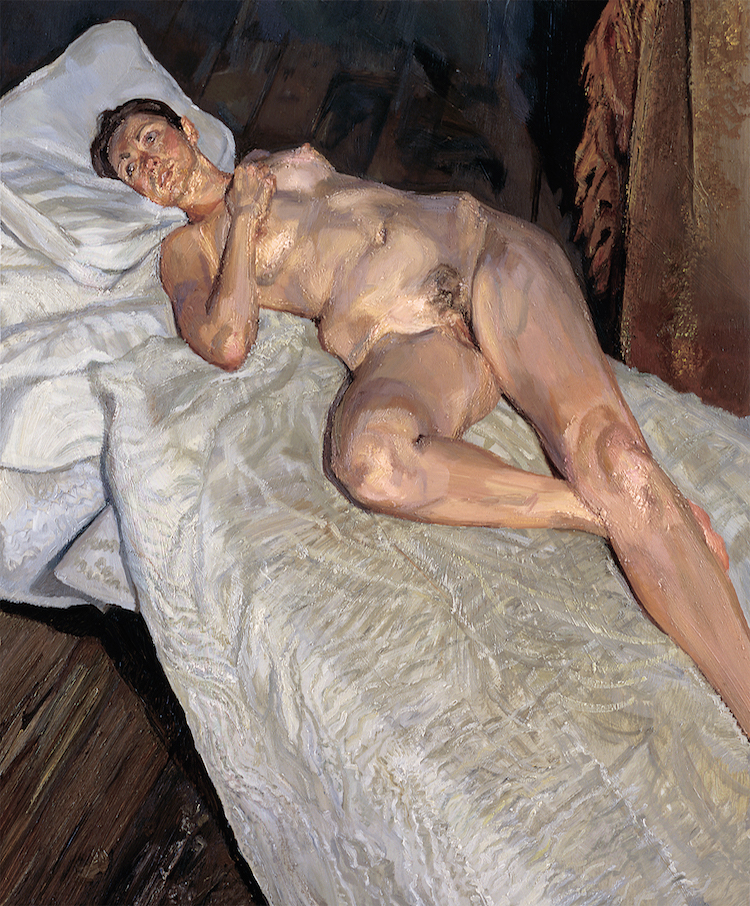

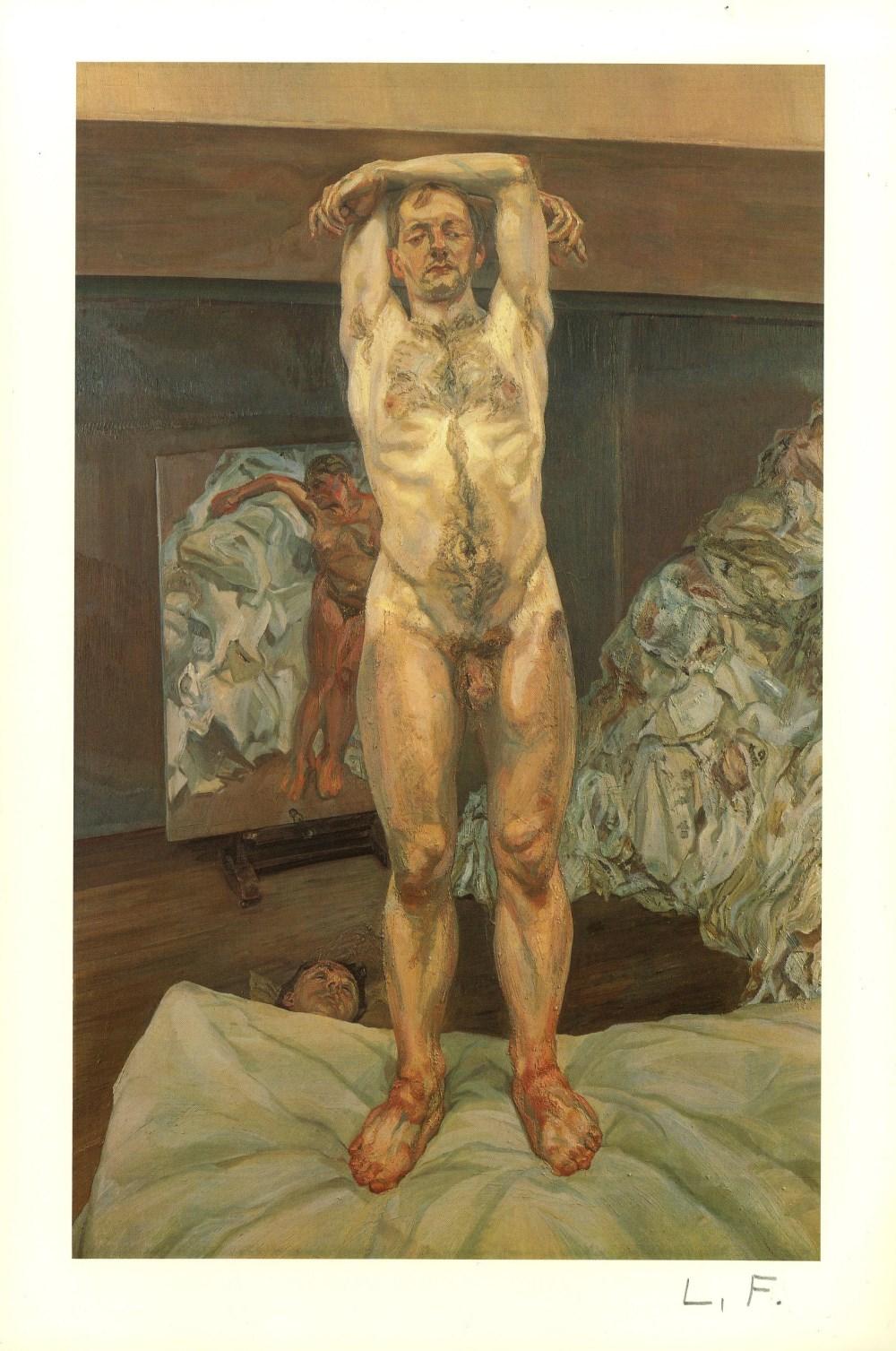

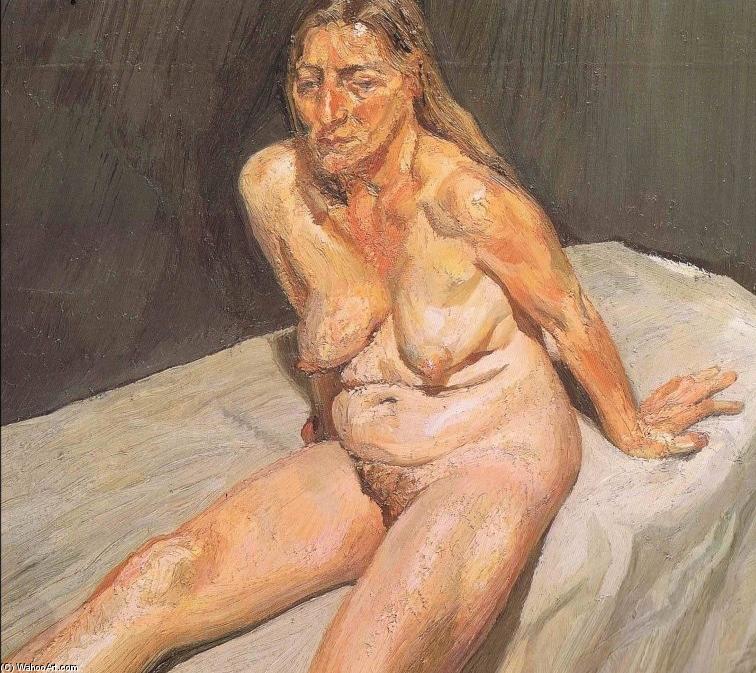

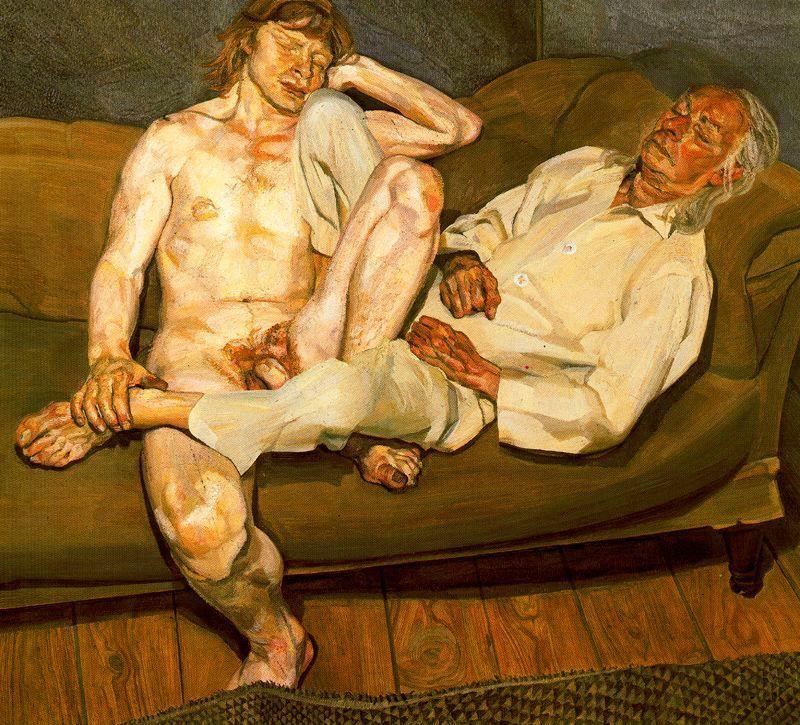

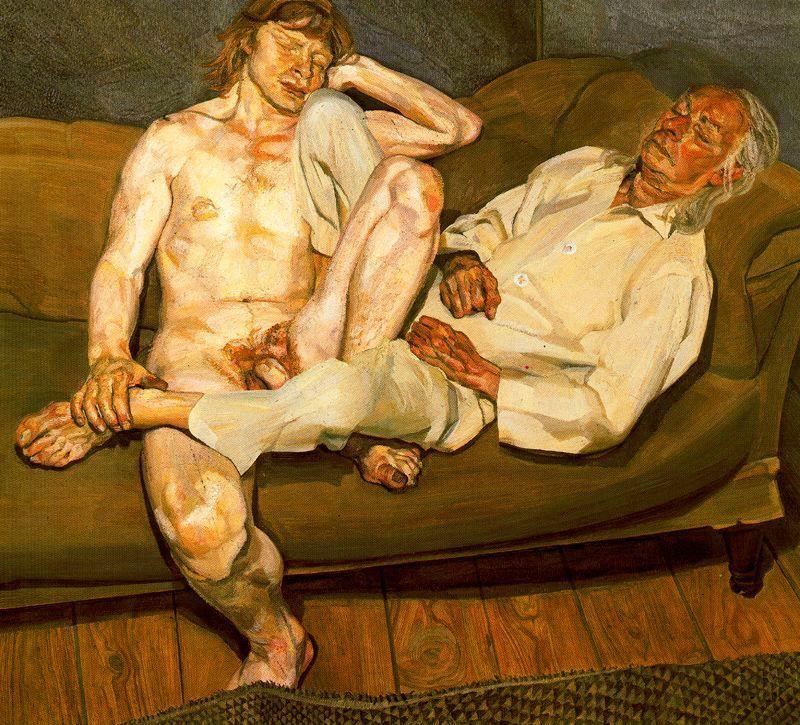

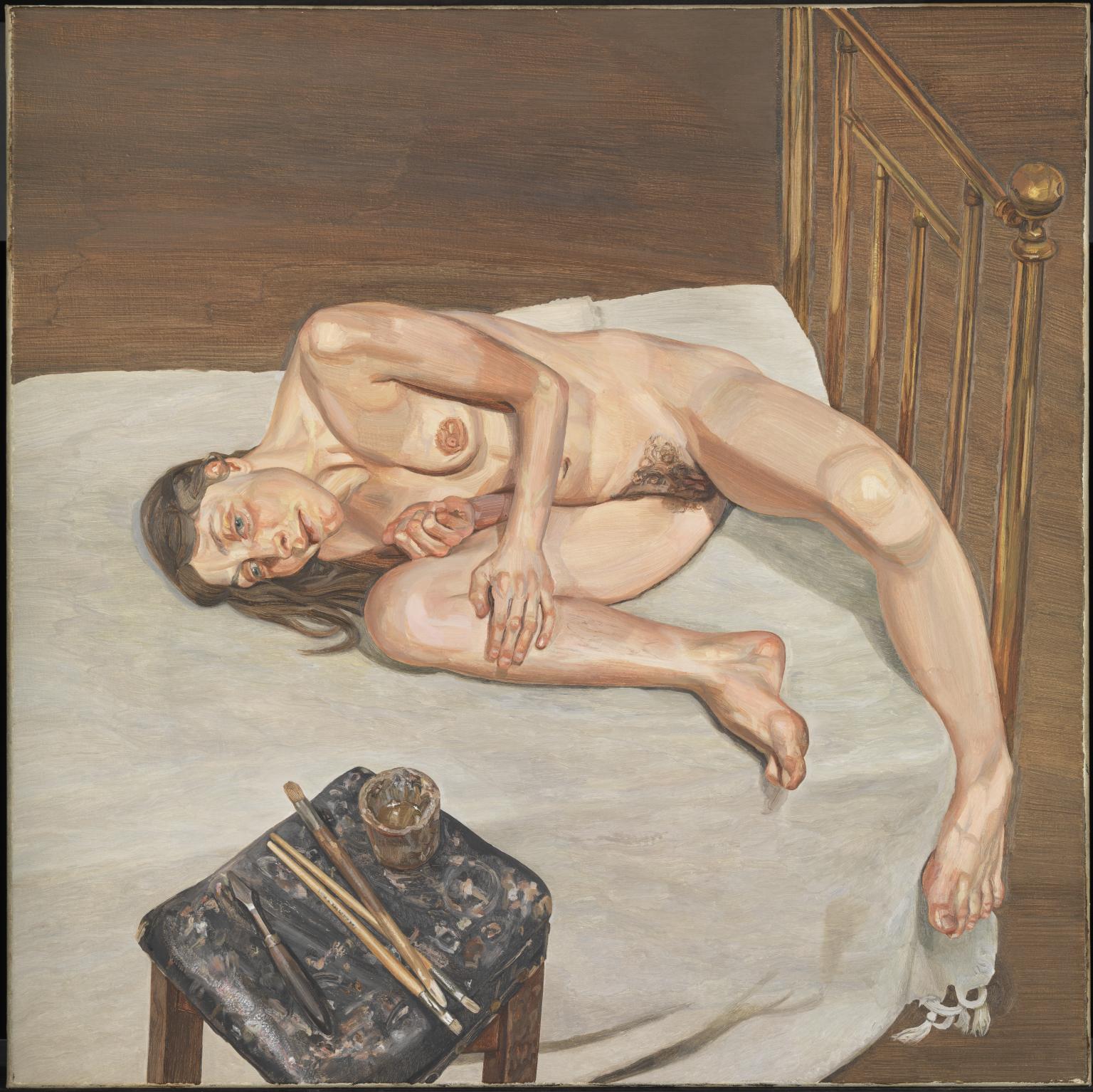

Freud’s nudes are Freudian in another way. Usually the recumbent or sleeping nude in art is highly eroticized, as with all those Venuses in Ingres or Giorgione. They are allowing themselves to be gazed upon without having to be present at the scene. But sleep, for Freud’s figures, doesn’t involve an absence of attention that allows us to gawk—it evokes the presence of their own inner attention, which compels us to recognize them as similarly human.

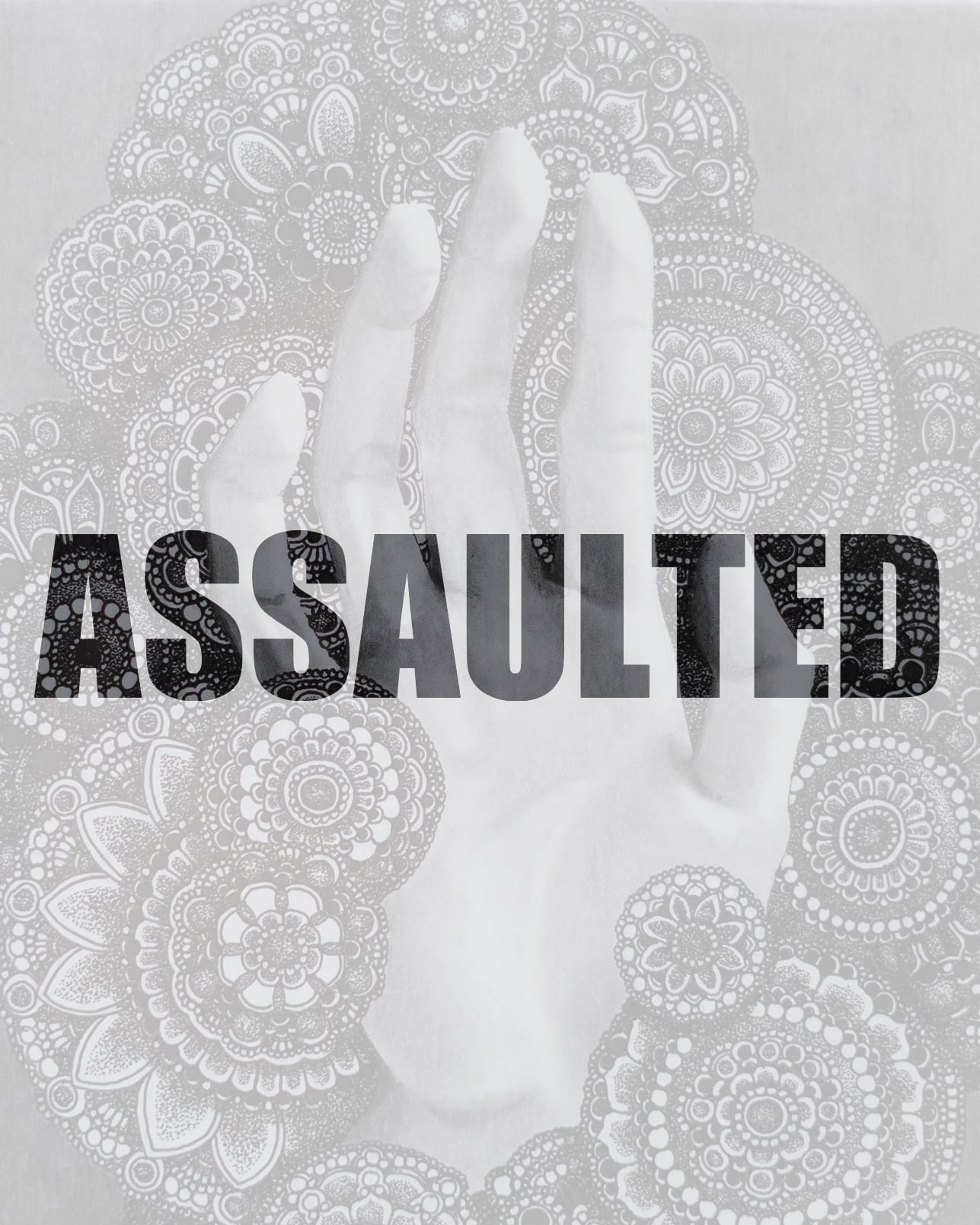

During his lifetime, Freud would change the way people viewed bodies. He filled his canvasses with figures rarely given space elsewhere: fat bodies, ageing bodies, queer bodies, exhausted bodies. Often, his portraits were described as ruthless, pitiless, clinical, and cruel, while others saw them as intimate and honest records of humanity. He described himself as “a sort of biologist”, one who is interested in the insides and undersides of things. He turned his scrutinizing eye on his own changing body at every stage of his life, experimenting tirelessly with strange angles and arrangements that pushed the boundaries of self-portraiture. Freud’s practice is deemed as a resilient exploration as witness to those around him and to his own existence.