An Interview with Krista Nogueras: Collecting Teeth

Published August 25, 2021

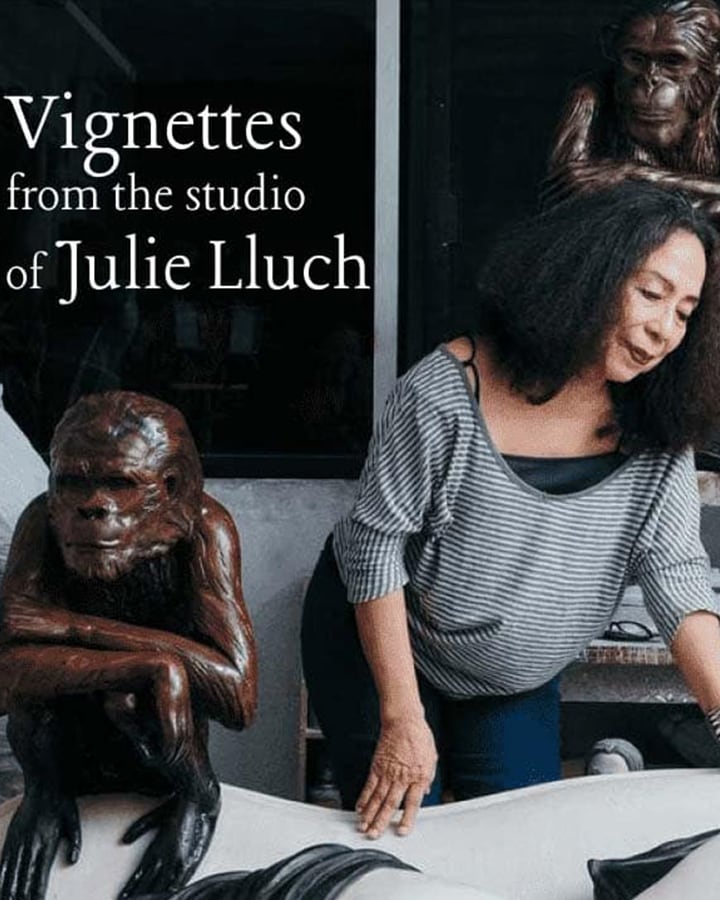

Filipina contemporary artist Krista Nogueras likens working with clay to self-mapping. It’s something made apparent in her careful consideration of the forms and imagery transposed into her stoneware pieces. Not limited to ceramic serpent like forms, Noguera's sculptures are based on her experimentations and structures from memory and from nature. They reach as far back as childhood for their visual vocabulary and even deeper into myths that suggest psychological states underneath the human experience.

Three of Krista Nogueras’ sculptures can be seen in the Little Big Art Show, an online art exhibition from Vintana.

In this interview with Vintana, Nogueras talks about the sources for her art and their resulting forms. These include her attraction to binary sensations, such as fear and fascination, and themes, like struggle and self-transformation. Such concepts guide her manipulation of clay into forms taken from fragments of nature, animals, and the human body. She also talks to us about experimentation in the ceramic making process and its different stages. She explains how it’s a process with weighty personal significance for her.

Krista Nogueras works predominantly with stoneware using traditional hand building techniques as her backbone, while exploration and experimentation are fundamental to her practice. She combines surface and form with various stain and glaze painting, print and mark-making techniques. Nogueras earned her BFA from the University of the Philippines, Diliman in 2009. She has exhibited her work locally and internationally. Her first solo exhibition Lake Predicament at Artinformal Gallery was shortlisted for the Fernando Zobel Prize for Visual Arts at the 2019 Ateneo Art Awards. In 2018 Nogueras participated in a month-long residency at T U Collab in Singapore.

Can you tell us about the visual influences that go into your work?

All the images that made an impact when I was a child are still naturally incorporated into my work or visual vocabulary. Growing up, my dad had a construction studio at home. And besides his wood works, I recall piles of wood, metal scraps, and remnants of materials that became pieces for accidental collages. This made a long lasting impression when it comes to appreciating and loving nuances in nature and space.

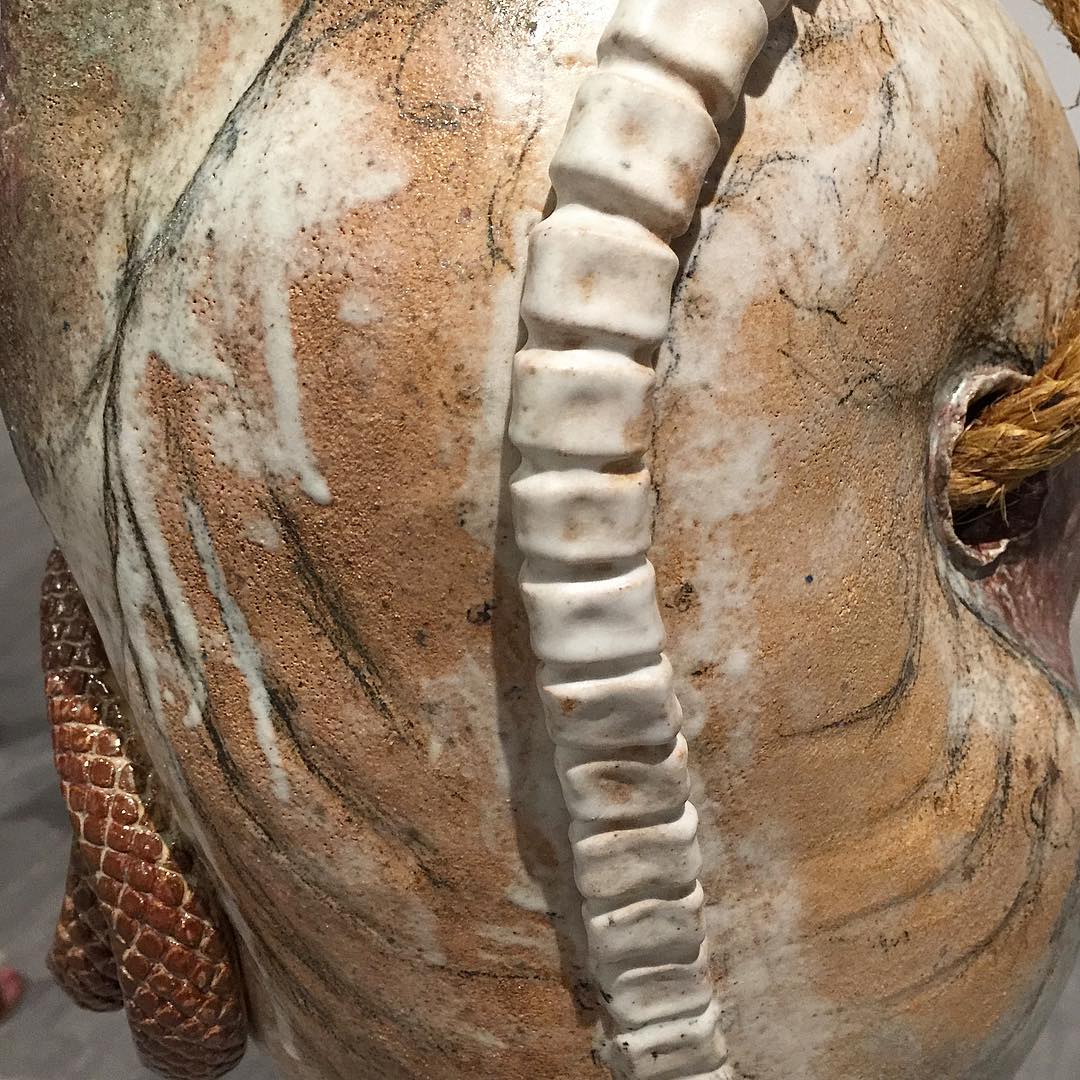

Anatomy too has had a similar impact. I'm drawn and fascinated with the ebb and flow of forms. And I love how learning, understanding, and viewing these interconnected forms has grown as I’ve matured. I’m also a sucker for textures, details, and the polar opposites of the spectrum. One such polar opposite is intricate details and negative spaces, which you’ll see present in the surfaces and forms of my works.

Since I was a child, I was drawn to macabre stuff. For instance, I used to collect my teeth and the bones of chickens, fish, frogs, anything I could get my hands on. It was a childhood fascination or a hobby to dig up soil for lizard eggs, which I would keep in bottles. My love for these sorts of things has resonated in what still interests me as a sculptor.

How did you come about the forms in your stoneware? Some seem to have unsettling natural sources. For instance, could you tell me about your sculpture called Brute Florescence?

I am keen on creating uneasy, uncomfortable, distorted, and confusing forms that give value on the journey of the work along two spectrums: process and the play of shapes, contours, textures, and finishes that subscribe to polar opposites, such as fragility and stability.

At times, my pieces employ ceramic collage in varying degrees of combination and permutations. Raw anthropomorphic sculptures are inspired by human figures, wild animals, and nature. For me, these images represent states of metamorphosis and conflict.

To explore the relationship between metamorphosis or transformation and conflict in my pieces, I work with notions of beauty, light, and pleasure that results from decay, suffering, and pain. In recalling my past experiences or emotions in my pieces, I could prompt my viewers to reflect and question their own perceptions of fear, suffering, and anxiety.

My sculpture, Brute Florescence, was part of “Recipes,” an Art Informal group show in Sept. 2020. The piece reflects how I have been adapting to the new normal and represents the concept of personal sanctuary/spiritual place as a conduit, a focused portal to converse with, contemplate on, and confront my own inner demons. It’s something I wanted to marry with the concept of discomforting shifts. In other words, this sculpture whose form is taken from an isolated upside-down chiropteran chrysalis embodies both self-transformation through struggle and sacred shrine.

I think that the pandemic has forced our psyches to shift perspectives. Ironically, being forced into isolation has come with the opportunity to transform our personal space into a chrysalis of evolution. This chrysalis has allowed us to wrestle with our fears, make peace with ourselves, reassess our purpose, and embrace this great change. The pandemic reminds us of the fragility of life and it amplifies our core values, both the good and the bad. Facing our dark side and embracing it poses an essential step towards wholeness and transformation.

The chrysalis form in Brute Floresence is combined with the form of a bat, since one of my inspirations in this is the white-nose syndrome affecting hibernating bats. This condition has resulted in the dramatic decrease of the bat population in the US and Canada. It has also forced bats to evolve to fight off the disease. This forced evolution resonates with me as it echoes with our situation.

What about the recurring serpentine forms in your work? What do you think keeps bringing you back to that?

Serpents are disconcerting and disturbing. I love embracing this discomfort and I am pulled to the mixed feeling and sensation of opposing forces like how you feel the shivers and being spellbound at the same time. The serpentine form represents these polar opposites.

I am also captivated by the many connotations of serpents. They are powerfully connected to life force. They evoke both fear and fascination at the same time. They have the ability to kill and the power to heal. There is both growth and great discomfort in the molting stage of snakes.

And then there is also Ouroboros, a great mythical serpent that is one of my favorite symbols. I love how the Ouroboros eats its own tail to sustain its life. It’s like there are natural sacrifices of the past needed in order to achieve renewal in one’s life. This polarity of sacrifice and renewal resonates with me and attracts me to the form of the serpent. It speaks of how one can move past stigma or manage fear and anxiety and even become desensitized to those debilitating feelings.

I’m also fond of making uncanny/primordial forms and emulating unsettling environments. And often, serpents symbolize the existence of the primordial force that is powerfully connected to life.

I also keep returning to the serpentine form because of the movement and flow of its body. It’s a form upon which I can refer back to in order to create or generate new forms.

How do you go about making studies for your sculptures? Aside from handling clay, what other processes go into this?

Depending on the situation, I do a rough sketch of the form on paper or sketch directly on clay. Sometimes I do no studies at all, forming the clay very intuitively.

Ceramics, on the other hand, can be a very tedious yet intimate and grounding process. Even before I can manipulate and handle the clay (mostly stoneware clay), I need to prepare it for optimal use. This preparation includes reclaiming and wedging, a laborious but very essential preparatory step.

Once the clay is ready, I work on it using traditional hand building techniques as the backbone upon which to explore and experiment. I love experimenting and bypassing traditional rules of ceramics -- like adding various organic materials and infusing them into the medium or using non-traditional methods to form my pieces. I’m keen on challenging and pushing the boundaries of clay when it comes to form, surface, and formation.

After working on the form of my piece, drying can then take place. Drying is tricky because it needs to be slow and even. Drying quickly and carelessly may lead to cracks when the clay is fired. Drying time usually takes 3 weeks up to months depending on the size, structure, and thickness of the clay.

The firing and glazing part of the ceramics process is a blend of science and art. I fire my pieces twice. The first is called bisque firing which usually takes around 8 hours. Once complete, I can then apply my glazes. The second firing is called glaze firing which takes around 12 hours or more.

The overall experience is very spiritual for me. You get to collaborate with nature, work with earth, water, wind and fire. It has its own element of wellness and spirituality. Whenever I work with clay, it feels like I'm tethered or rooted. I feel connected to being human and being real. I feel connected to the world, if that makes sense. It grounds me.

It is also my intention to create works, which create coherent dialogues about process and materials, with neither taking precedence over the other. They are a marriage of those two elements, where the process involved is as important as the material used. This tramples upon notions of ceramics as craft due to its material being seen as less than fine art.

Some of your ceramics have a certain rough texture. They remind me of sketches and come across as a ghost-like effect. Sometimes, the texture simulates natural surfaces like leaves, scales. Could you tell me more about this?

Besides the visual influences for the textures of my sculptures, I use different found materials as tools for texturing and forming. This accounts for how I achieve different surfaces. I also combine surface and form using different techniques of mark-making, print-making and various stain/glaze painting.

Could you tell me about the basis for “Moulting,” the exhibition of works you created at your TU Collab Singapore residency?

Our SG residency show was entitled “Variables of Function,” featuring ceramic pieces that focused on the question of function.

To me, the meaning of function, in relation to ceramics, goes well beyond the archaic definition of utilitarianism, which speaks of the practical purposes of a piece of work. I do not believe ceramic pieces should be purely categorized based on our preconceived notion of function, because an object can extend its relations in the physical sense. For instance, a handmade cup for drinking can also be an important piece of art and vice versa.

Handmade functional pottery, for example, takes time, care, and skill to master. There is hope that a particular object will somehow build a connection between the spectator and the supposed intended purposes of the creator. And so, working with ceramics, function becomes a term that is fluid and not necessarily a category that limits the medium to a clear practical use.

However, the artist’s intention with an object can also shift one’s perspective of it, even criticizing and shifting the definition of art.. In a similar turn, I believe that function can also be dictated by the context and the setting of how the piece is used/treated over time.

Though, a certain piece might in the beginning function as a vase. Through time, this vase can function in a more evolved way, one that can connect and change one’s perspective of certain things. For example, a vase displayed inside someone’s childhood home for years can become a psychological marker of someone’s experiences growing up. The function becomes similar to how pieces of fine art can connect with humanity in psychological, emotional, social response terms, and so on.

Take a look at Krista Nogueras’ three ceramic and stoneware sculptures called Wildling, Becoming, and Assiduous Uprising, only at Vintana’s The Little Big Art Show.