Edvard Munch: Inside the Madness of the Method

Published June 28, 2022

“I can not get rid of my illnesses, for there is a lot in my art that exists only because of them.” -Edvard Munch

There’s a hidden basement in Munch Museum where you can find madonnas and vampires, lions and tigers stashed away with hefty white blocks from which they were printed, still stained with printer’s ink. Being there feels like being inside Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s brain.

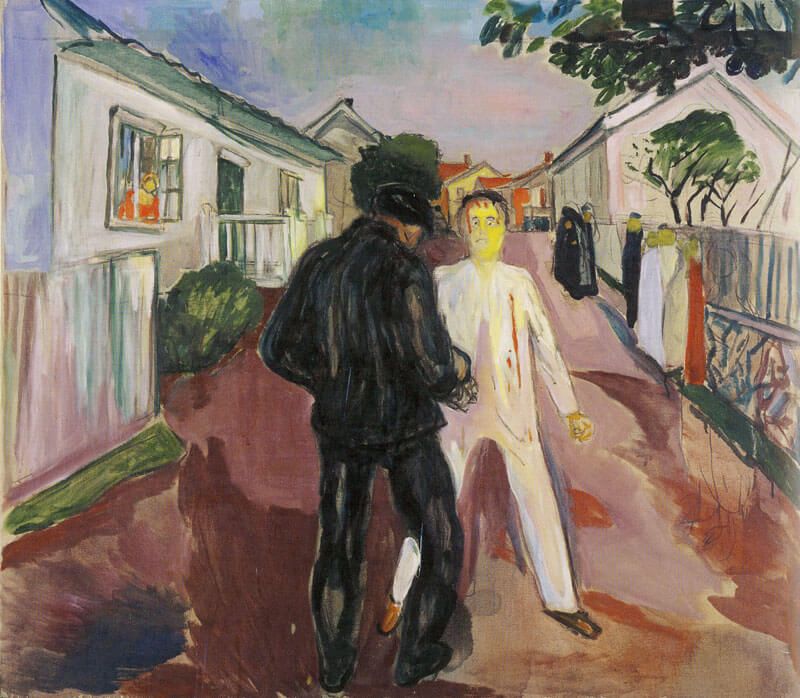

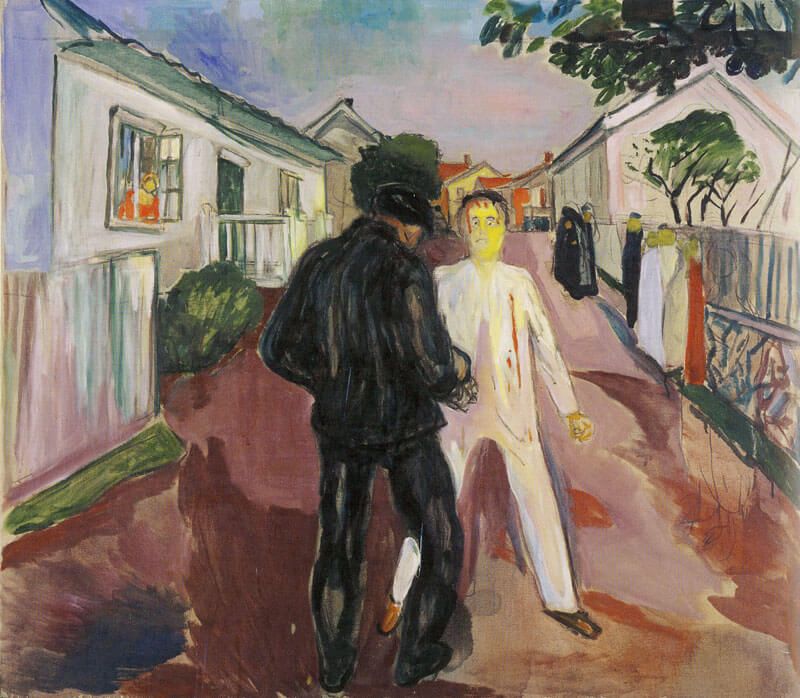

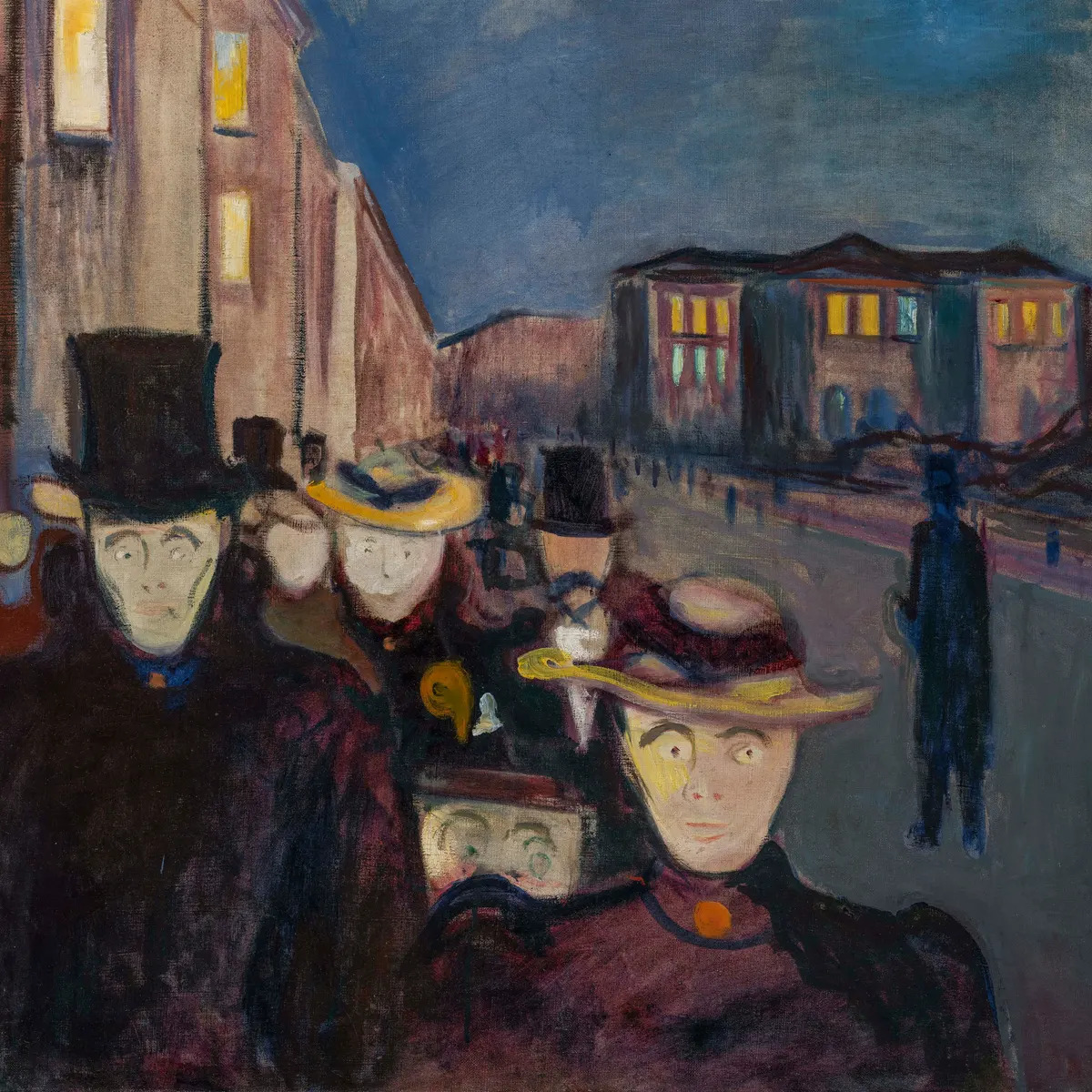

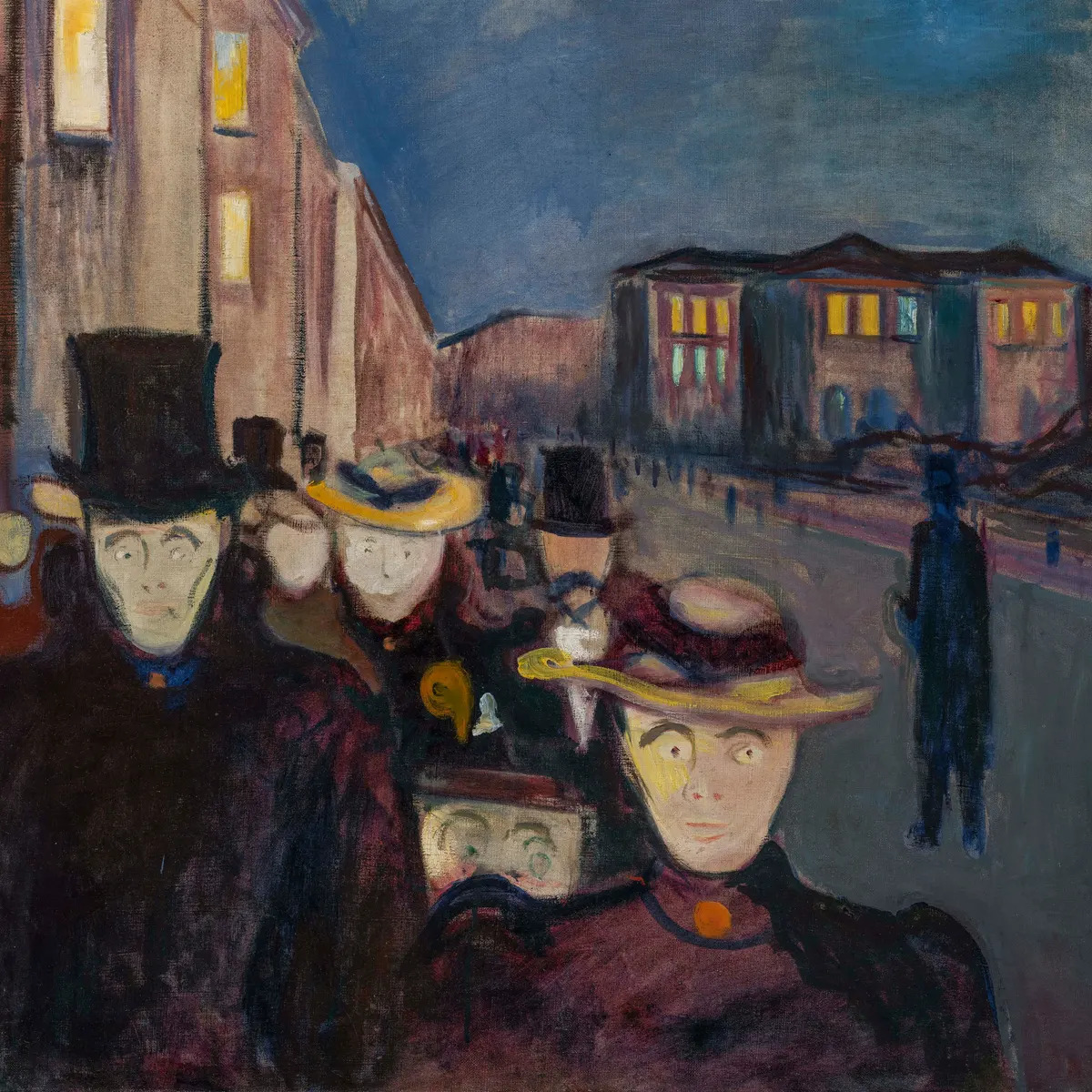

Many of Munch’s works are about life and death, love and terror, and the feeling of loneliness. Often, viewers would note that his work pattern focused on such themes. These emotions were depicted by the contrasting lines, the darker colors, blocks of color, somber tones, and a concise yet exaggerated form which depicted the darker side of opus. Fascinated by psychology and haunted by mental collapse, Munch considered Sigmund Freud, a close contemporary, as one of his greatest influences. Munch understood the power of suggestive experience and the irrational forces of the mind. He was often preoccupied with matters of human mortality such as chronic illness, sexual liberation, and religious aspiration.

In his early work, he used lighter tones compared to his later work and was also influenced by the French Impressionists of the 1870s and 1880s. Though he would shift to darker subjects in the latter half of the 1880s, he was extremely prolific and continued painting bright landscapes and subdued portraits of family members and friends throughout his career. Munch came of age in the first decade of the 20th century, during the height of the Art Nouveau movement and its characteristic focus on all things organic, evolutionary, and mysteriously instinctual. Similar to his near-contemporary Vincent Van Gogh, Munch aspired to record a kind of marriage between the subject as observed in the world around him and his own psychological, emotional and spiritual perception.

In the 1880s, Munch actively sought-out a bohemian lifestyle and during this period of his life, he discovered the writings of the anarchist philosopher Hans Jaeger who headed a group called the “Kristiania-Boheme” which was a central principle of a larger anti-bourgeois agenda, the group advocated liberal sexual behavior or what we know as the “free love”, and the abolition of marriage. The two formed a close friendship and Jaeger encouraged Munch to draw more personal experience in his work. In 1889, Munch traveled to Paris on a state fellowship to study in the studio of Leon Bonnat, a French painter and professor. Munch began to draw in Paris after Impressionists, such as Manet, and Post-Impressionists Gaugin, Van Gogh, and Toulous-Lautrec.

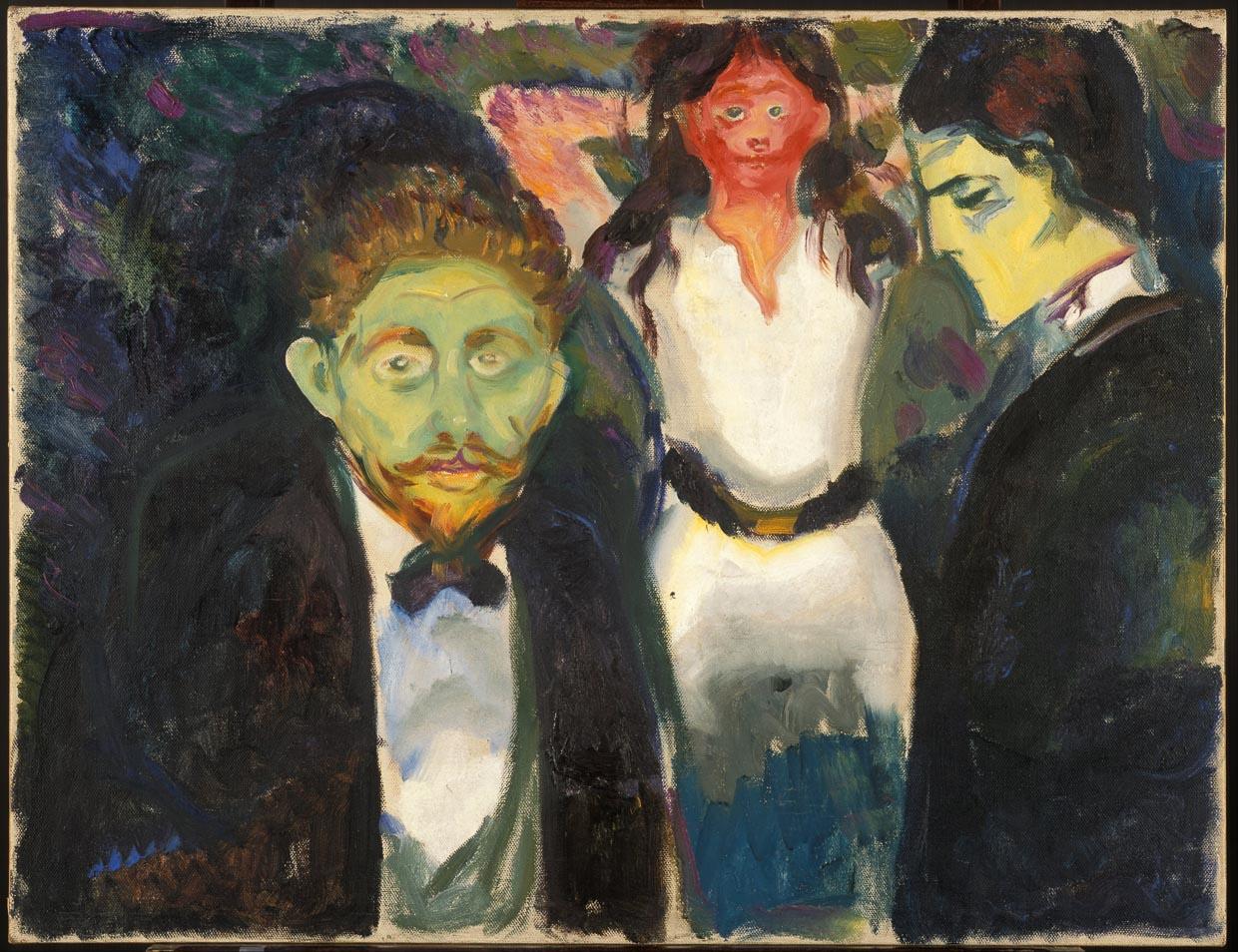

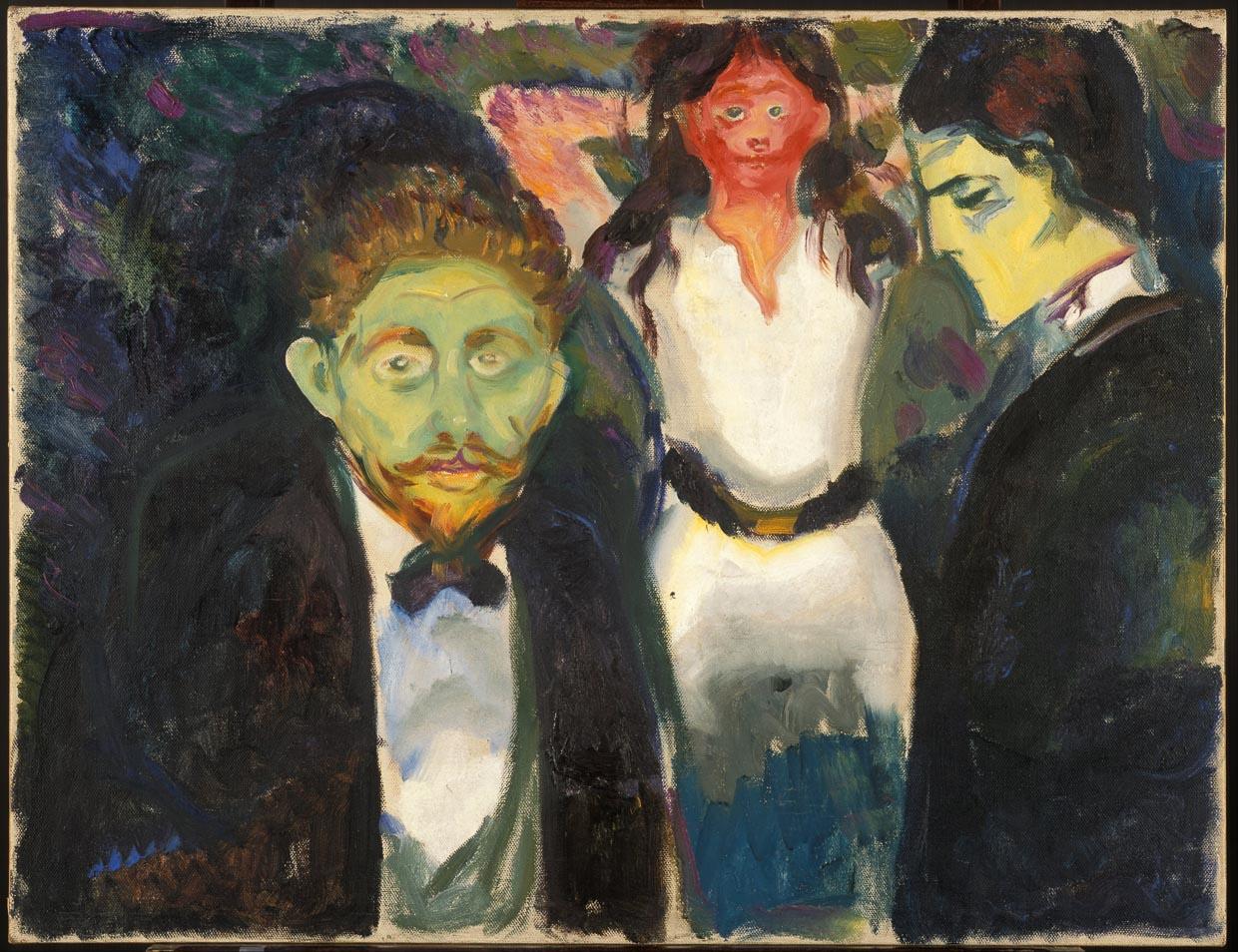

In 1892, Munch was invited to be the subject of the Union of Berlin Artists. His works created much controversy due to their radical color and brooding subject matter and the exhibition was closed prematurely. Instead of bringing him down, Munch capitalized on the residual publicity and his career flourished as a result. The following year, he exhibited a group of six love-themed paintings in Berlin that would eventually evolve into the larger renowned series “Frieze of Life - A Poem About LIfe, Love, and Death”.

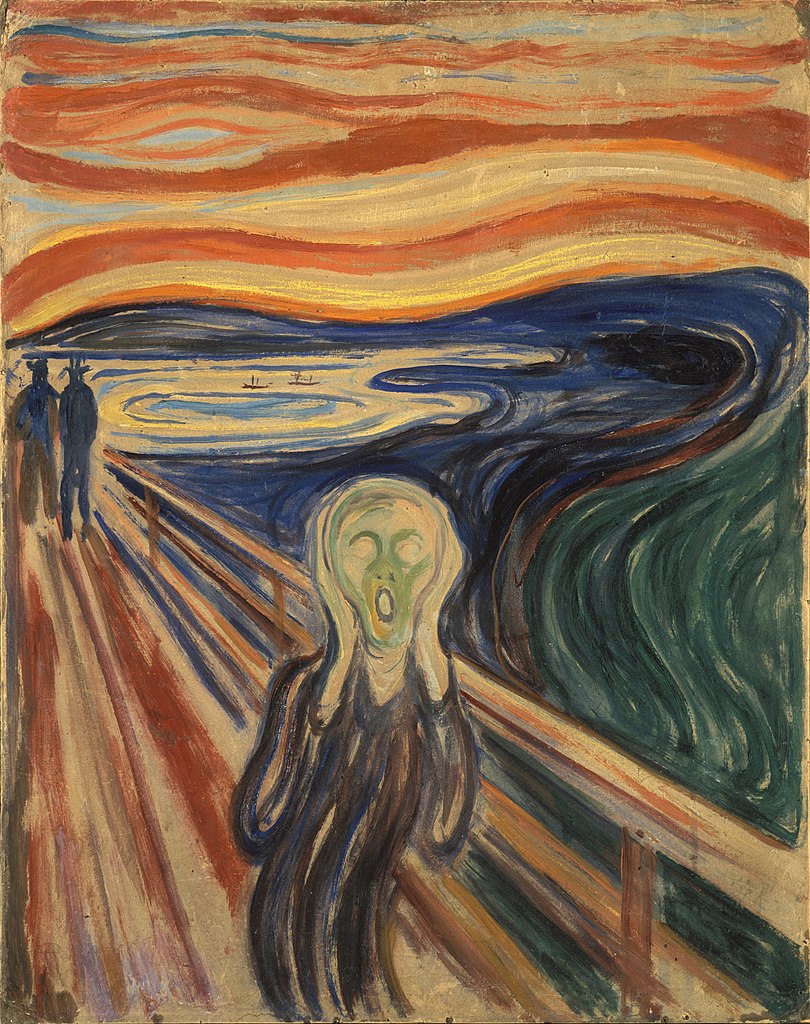

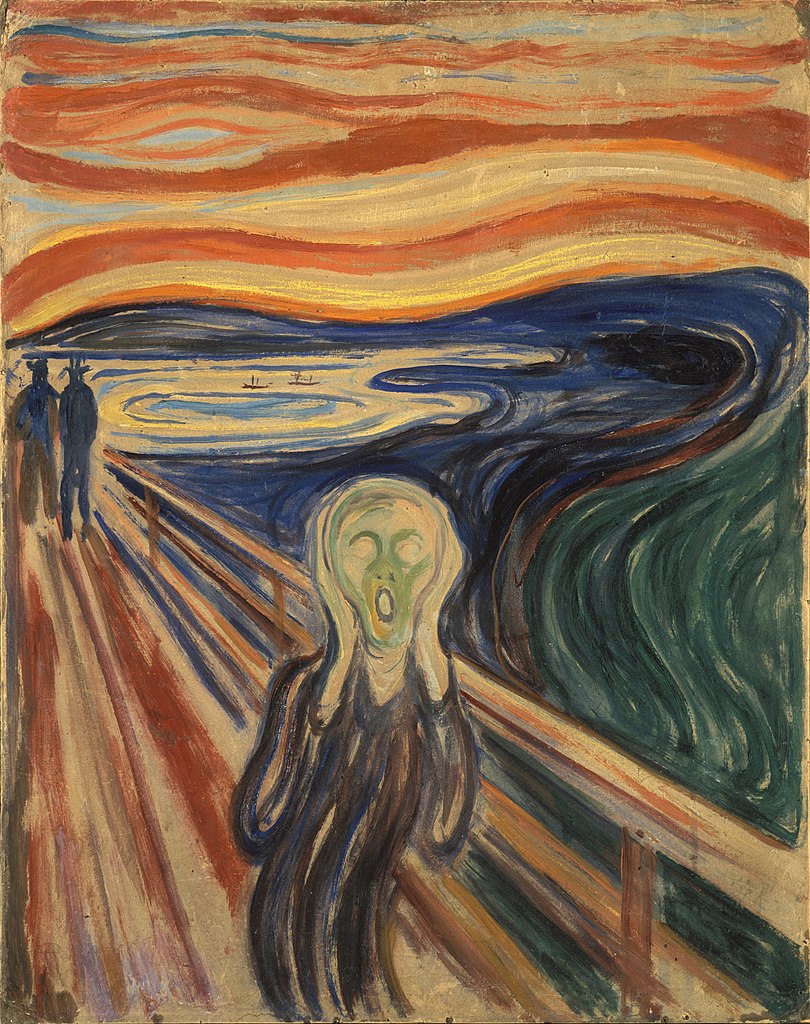

Munch created his signature painting The Scream in 1893. Inspired by a hallucinatory experience in which Munch felt and heard a “scream throughout nature”, it shows a panic-stricken character, simultaneously corpse-like and reminiscent of sperm or a fetus whose contours are echoed in the swirling lines of the blood red sky. The painting expressed anxiety raised to a cosmic level ultimately related to the ruminations on death and the void of meaning that were central to Existentialism. The Scream was among his signature works which he created in quick succession of each.

In his later years, Munch continued drawing from his daily life and personal experience and shun overt themes of loss and death. An exception was Munch’s focus on his own mortality as was reflected in his much later works until his death.

Sources: edvardmunch.org, The Art Story