Art Lovers

By: Masi Oliveria

Published April 20, 2023

All was fun and games before Jack and Maggie came. Or maybe the real game only began when Jack and Maggie arrived. They were like parents breaking up a teenage party. But boring parents they were not. They supplied copious amounts of cocaine, caviar and champagne and we could have as much as we wanted so long as we were big enough to take a seat at the Grown Ups’ table.

Back then, our little group met for dinner and drinks, especially drinks, at a hole-in-the-wall that served barbecue and beer, to gossip and talk about art. In those days, conversation flowed so easily like a game of ball going round and round the table and time and time again we would fall into hysterical fits of laughter. There were tantrums and fights, and sometimes sticks were thrown and bottles were broken, but altogether, nothing was taken too seriously, although we did talk about serious things.

We talked about the Nazi’s degenerate art exhibit one moment and Ovid’s Ars Amatoria the next, The Fall’s lyrics, noise music, Catholic aesthetics, and organic gardening. The death of cool and avant-garde zombies. We dissected dystopian literature and utopian cuisine, the mythology of painting and the economics of porn, who was hot and who was nuts, Nikola Tesla and the Sumerian civilization. Jump cut to the history of punk and the Origin of the Species. The rules and regulations of chaos magick, DIY furniture and semiotics. The psychology of serial killers and sex workers. We investigated pataphysics and the raw diet, spiritual enlightenment and national schizophrenia, the art of the insane and Brutalist architecture. And deconstructed the joys of alchemy, off-the-grid living, underground comics, and the poetics of space. No topic was off-limits, except the art of those who were there. Of course, we discussed, at length, the art of those who were not present.

Those were sublime and pure days when plans and schemes came in torrential downpour or a soothing tranquil drizzle, and all those talks would materialize into artworks in the next exhibit or even the next day, executed with a hangover. We borrowed and stole each others’ ideas with a nudge, a wink and a ha-ha.

The love story of Adam and Bel began in that hole-in-the-wall. They started out as drinking buddies. Adam was a painter with a baby face and a figure like the statue of David. He made stark abstractions with esoteric themes poised on the knife’s edge of pleasure and pain. Bel had the face of a Holy Virgin with big boobs. She was nice and unfussy to the point of becoming a welcome doormat. She depicted scenes of adolescent sexuality and adult misbehavior.

One night, while we were debating the meaning of nothing, Adam leaned over and whispered in Bel’s ear, “What’s the difference between an orange and an erection?” Bel couldn’t suppress a giggle. “I don’t have an orange,” Adam told her. They were inseparable ever since. High on love, time stretched to the infinite. They lived together in a tiny apartment with a gruesome toilet and barely made rent from the little that they made from the art they barely sold. To make ends meet, Bel designed T-shirts and Adam painted signs. But they devoted most of their time to making art, making love and going to art shows. Drinking with friends was their highest form of art.“He got me at erection,” Bel would later recall.

The night that Jack and Maggie showed up, our group opened an exhibit at an underground gallery. After the show, we all went to our hidey-hole to drink some more. In the midst of our revelry, Jack and Maggie came in like two dark stars that sucked the energy in space. A kind of fever bubbled on the surface, and the center of gravity shifted. They sat three tables away from us. Our talk became strained, self-conscious and devolved to petty complaints about the rude waitress or that dumb security guard, to tedious quibbles about the evil people in power and the rotten government. They bought us a round of drinks and we cheered them but kept our distance.

The next month, the gallery called and told us that they sold all the works in our show. We were beyond the moon and immediately blew off our money on a trip to the beach and a bag full of psychedelics. It turned out it was Jack and Maggie who bought all our works. We didn’t know it then but it was only the beginning of the dangerous games Jack and Maggie liked to play.

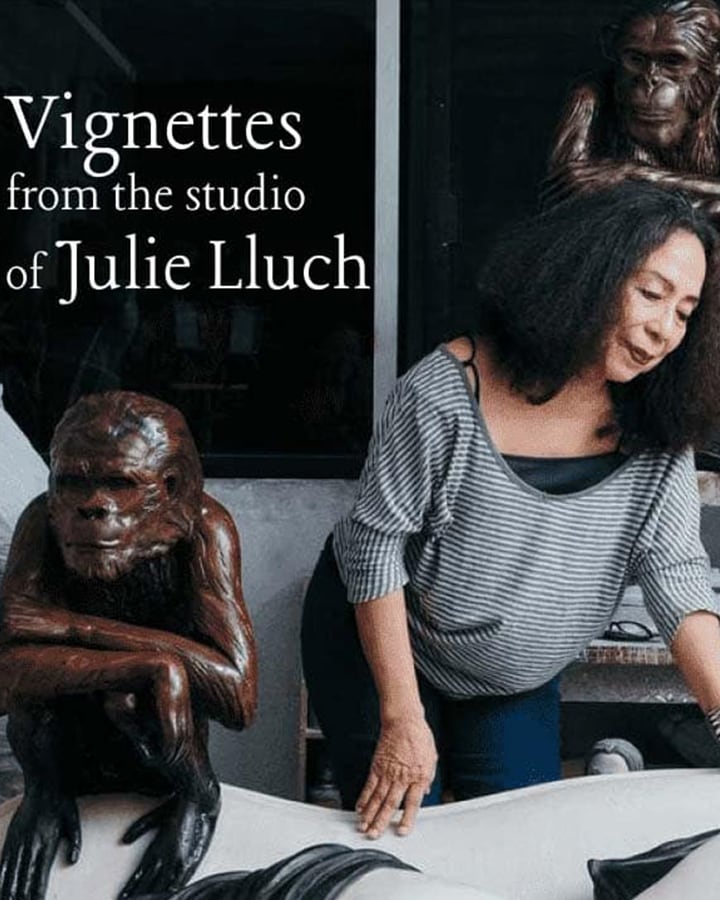

Maggie was not at all pretty, she looked awfully plain and homely: a fisted-up simian face, bug eyes, bulbous nose and a thin crooked mouth. Yet this woman with a sad-sack and Michelin Man belly had the most elegant ears and slender erotic hands. Jack idolized her and she attracted a plethora of prominent people. Maggie’s secret weapon was her supernatural senses. “I may not be as beautiful as Bel,” she once told Adam, “but I am sure I am much more alive than she is.”

The über rich and stunning Jack had never dated anyone less than gorgeous before he met Maggie. He thought she looked hideous when he first saw her, but he underestimated her spirit. Before he knew it, Maggie bewitched him with her glorious vitality that could revive a corpse. Her bright conversation made him roar with laughter. “Your mama is so classless,” Maggie whispered in his ear, “she could be a Marxist utopia.”

Defying his family, Jack married Maggie on the sly. She systematically smashed every social code in Jack’s soigné circle. She was an obstreperous rule breaker and troublemaker who enjoyed carousing under the horrified gaze of Proper society. She told bawdy jokes, smoked joints, and brazenly flirted. She arrived at dinner parties bedecked in jewels from her admirers. Once, she went to an art opening with a lion named Hex, appeared at another show in Persian dress on the back of an elephant, and barreled through town in her Aston Martin, scattering terrified pedestrians and swearing like a sailor in four languages.

All types of men succumbed to her spell and accompanied her everywhere. In Venice a blond Adonis squired her through the palazzi, and in Bombay six men motored out to her ship with gold and silver crates filled with Krug Vintage Brut. At home she acquired so many devotees. Ten or a dozen of the leading male members of high society flocked to her like flies around honey. Amid his wife’s flirtatious romps, Jack remained the smitten, faithful husband.

Jack funded Maggie's passions. Fortunately, she championed our art and collected our works. “They bring me so much pleasure,” she said, “You know that feeling of butterflies when you first meet that special person and you can’t wait to see them again? That’s how I feel when I look at these works. It’s intense, mind-bending, infatuation, except they don’t buy me dinner!”

It was Maggie who bought us dinner. She gave us allowances, lent us spaces for studios, treated us to fancy restaurants, designer clothes, expensive books, and trips abroad. Every acquisition of hers involved “falling in love” in a way that the artworks became essential to her and she would do crazy things for art.

At first it was about the art. We thought we were punching a hole in the collective unconscious and kicking the door of social awareness. We were having a party while revolutionizing society. We believed so deeply in the integrity of our mission that we thought nothing could corrupt or compromise our art.

We barely finished our works and Maggie and Jack would snatch them up. Soon other collectors followed and we started making obscene amounts of money. We moved to nicer digs and ceased exhibiting in the raw, unfinished spaces of underground galleries. We showed in polished commercial spaces that had terra-cotta floors and an Empire desk out front that put out a status symbol with no pretense of Bohemia. It was quite a difference from the small shows we used to have, where often, only our friends and family would turn up for the opening. Those days, we were basically making art for each other.

Under the patronage of Jack and the orchestration of Maggie, exhibit openings became red-carpet events with the feeling of a product launch—crowded, lavish and impersonal. The artworks also became lavish and impersonal, and transformed into brands and commodities. Those who thumbed their noses at the new establishment and insisted on making ephemeral, or otherwise uncollectible art, did so at the peril of their art careers, and bit the dust.

Those of us who were willing to play the game, the whole city opened up. We got into several lists, and everyday the invitations would come pouring in—openings, preview parties, museum events, galas, concerts, and screenings. We stopped going to the old haunt and moved to a fancy hangout—long wooden bar, paneled walls, scuffed parquet floors, tall windows, soft lighting, red wine, and sparkling cold duck. Every time we walked in, we were treated specially. In the bathrooms were toilet-paper dispensers that had flat metal trays on top that made it easy to cut up and snort lines of cocaine.

We started talking with our phones. We passed them back and forth to show photos of our kids or pets, shows and artworks, plants and food. We stopped looking at one another across the table and started crowding in on one another staring together at a tiny screen someone was holding up in explanation of a trip to Spain. Quickly our vocabularies shrank. Instead of summoning words, we tapped on images. We stopped finishing sentences. And in startlingly short order, we could no longer describe art or talk about ideas. When we did talk, we talked about collectors and their collections, how much an artist’s work was worth, who we fucked and who we knew, real estate and current events, investments, health insurance, legal matters and celebrities. It was still taboo to talk about the art of those who were there.

One night, a grand party was held in our honor on the outskirts of the city at the home of Jack and Maggie. A fleet of limos picked us up and drove us to a gated enclave. The property was completely enclosed with high brick walls and lookout towers. Armed guards patrolled the area, carrying machine guns.

When we arrived, our names were checked against a list and our limo scanned for bombs. The guards frisked us and took our phones, told us we could get them back after the party. Finally, the gates parted and we drove up a long road to a tall house of steel and glass. A huge steel sculpture of the Venus of Willendorf stood in the middle of the driveway.

Jack and Maggie had a penchant for exhibiting their art collection in unusual places. In the middle of the tennis court was a giant glass sculpture of their cat. On a concrete wall obscured by a steel beam was a photo collage of giraffes. They cut holes in the beam so that the viewers could see more of the piece. Encouraged to explore the house, we stumbled into the spa where we found an El Greco just outside a steam-room. Later we saw a Picasso mounted inside of a closet.

A glamorous crowd milled around—some were dancing, others were naked. Waiters in silk smoking jackets carried trays of champagne and oysters and offered guests a choice of marijuana, heroin or cocaine.

Maggie stood at the top of a massive staircase dressed in plunging black velvet, presiding over the gala. A crown of diamonds on long antennas bobbed from her head. One by one, the very important guests mounted the steep stairs and climbed down again to pay their respects as a grand symphony played overtures.

At the climax of the party, Maggie in her black dress and Jack in his sharp white suit strode through the great hall with an entourage of beautiful people. When they flung open the double doors, a collective gasp went up from the crowd. Inside was a soaring three-story courtyard lit by the moon and hundreds and thousands of lanterns. On the grounds and on the walls, were our artworks.

It was the incarnation of our dreams. An unknown pleasure of divine arrangement. We saw our conversations, arguments, laughter and blood trapped in the works, whispering and screaming at each other, alternating solace and anxiety, quiescence and ecstasy, warmth and distance. A visual symphony of despairing comedy, pathos, terror, and metaphysical giddiness. It was a religious moment, a gospel miracle. We had the queasy feeling of exhilaration and a shared intimacy of a group losing its innocence.

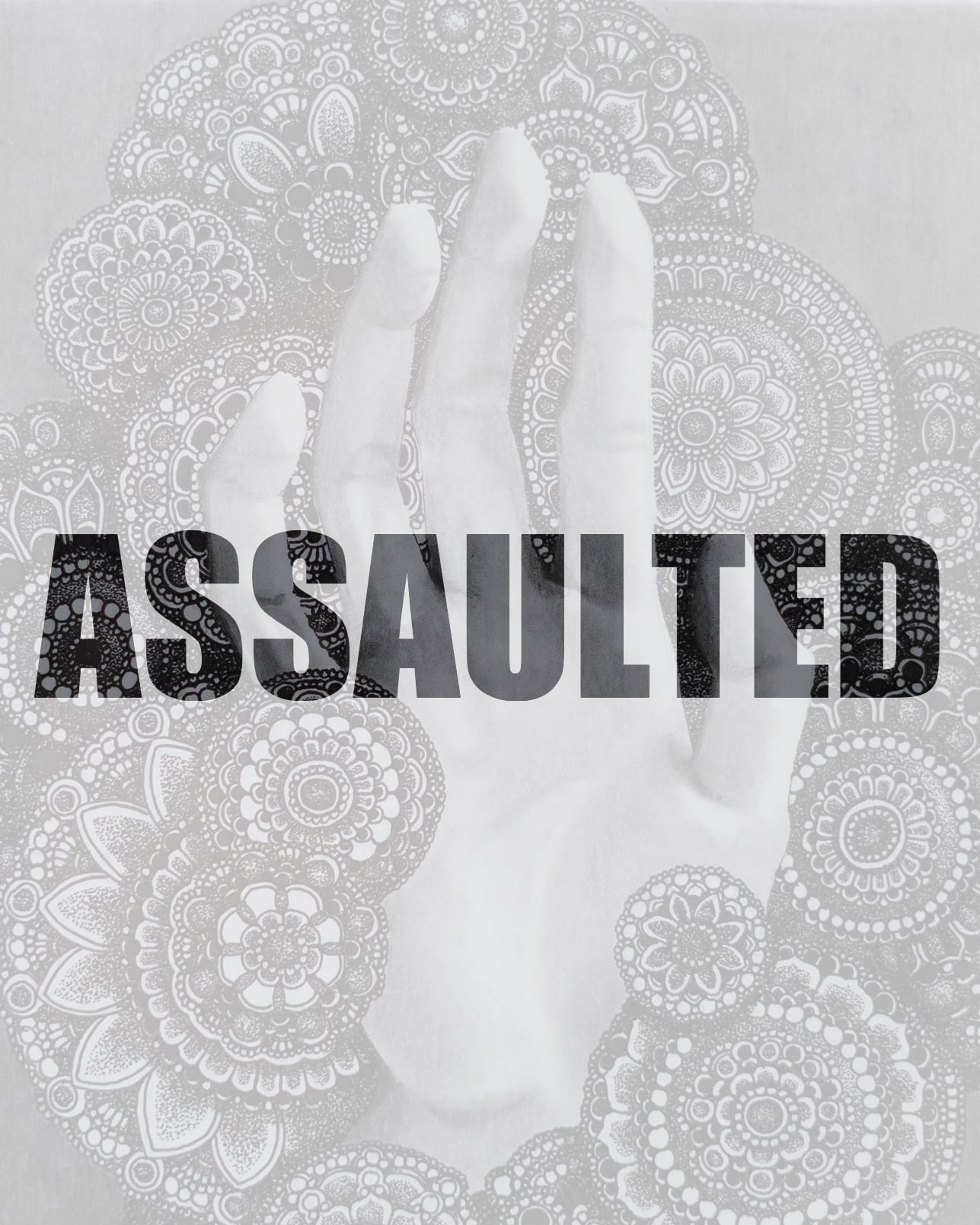

That night, we worshipped Maggie and Jack. Adam fell into Maggie’s trap. She rattled his bones, wooed him with ancient ur-spells, and took him to paradise. Poor Bel didn’t stand a chance against the numinous woman.

Adam and Maggie rode out in public in her Range Rover and monopolized each other at charity balls and events. They spent the summer together at her Northern estate, traveled to Africa, and wore matching hats. Thirteen years Adam’s senior, Maggie deployed the primordial lure of mother love. At their tête-à-têtes in her boudoir, she played the piano and sang to him in her voluptuous, mellow voice. “Love must be sought, cultivated and developed if we are to make a better world,” she would tell him, “Without art, love sinks into stasis and ennui. Love despises the lazy.” She nurtured his art and polished his star. Maggie created Adam. Adam was her work of art, what she called her “social sculpture.” And the rest of us were supporting actors in her serpentine play.

“I have been at the mercy of a kind of terrifying crushing and tearing of consciousness, unable to connect anything, to assemble anything in my mind, or still less to express anything,” Bel cried her heart out. She came back to the old hole and hung out once again with those who stayed and ate the dust, and insisted on making their jejune and obscure art. Unhinged and broken, she pushed herself out of the realm of fairy tale and lurid romance onto uncharted aesthetic territory. The open palm of desire wants everything, everything. And she desired, “Art that is there all at once. Like getting hit in the face with a baseball bat. Or better, like getting hit in the back of the neck. You never see it coming: it just knocks you down. A kind of intensity that doesn’t give you any trace of whether you’re going to like it or not.”